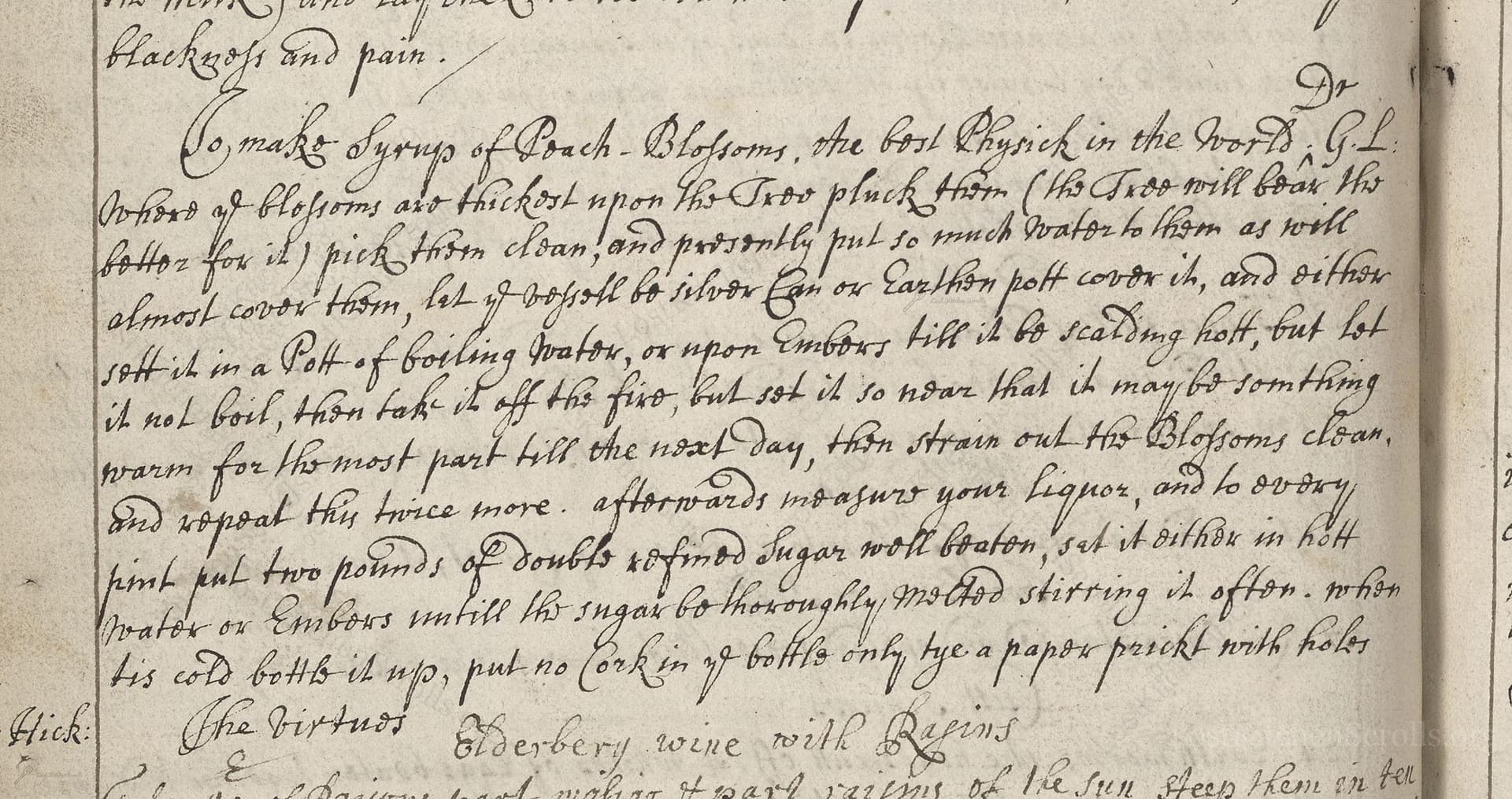

To Make Syrup Of Peach-Blossoms, The Best Physick In The World G.L

"Gather ye blossoms also thick as they stand upon the Tree pluck them (the Tree will bear the better for it) pick them clean, and presently put so much water to them as will almost cover them, set it either in hott water or on Embers till it be scalding hott, but let it not boil, then take it off the fire, but set it so near that it may be something warm for the most part till the next day, then strain out the Blossoms clean. afterwards measure your Liquor, and to every pint put two pounds of double refined Sugar well beaten, set it either in hott water or on Embers untill the sugar be thoroughly melted stirring it often. when its cold bottle it up, put not Cork in ye bottle only tye a paper prickt with holes."

Note on the Original Text

The recipe, written in plain, directive prose typical of late 1600s manuscripts, assumes familiarity with kitchen techniques and omits precise measures or times—quantities are given relative to the produce gathered, and timing is guided by observation (‘scalding hott’, ‘till next day’). Spelling is archaic but understandable: ‘Physick’ for medicine, ‘Liquor’ for any infused liquid, ‘bottle it up’ meaning pour into bottles, ‘prickt paper’ as a vented cover. Ingredients like ‘double refined Sugar’ refer to sugar purified to a very fine degree, alluding to the best quality available at the time. Such language reflects the oral and practical tradition of recipe sharing in early modern households.

Title

Receipt book (1687)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Unknown

Era

1687

Publisher

Unknown

Background

A charming culinary manuscript from the late 17th century, brimming with recipes that blend hearty tradition and a dash of Restoration-era flair. Perfect for those seeking a taste of historic feasts and flavorful ingenuity.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

This recipe hails from late 17th-century England, in a time when home remedies often blurred the line between culinary delight and medicinal practice. Peach blossoms were prized for their gentle laxative and 'physick' (healing) qualities, considered a cure for various digestive ailments, and a sweet syrup was a graceful way to administer such pharmacy to the household. 'V.b.363', dated approximately between 1679 and 1694, represents a manuscript tradition where householders (often women) curated collections of both recipes and medicines, reflecting the domestic and botanical knowledge of the era. The use of refined sugar—still a luxury ingredient—signals the recipe’s elite or aspiring context, while the careful method speaks to the high value placed on the blossoms and the importance of preserving their delicate fragrance.

The original maker would have used a small copper, earthenware, or pewter pot for infusing and dissolving the syrup. Gentle heat was provided by embers or a simmering water bath, as direct heat risked scorching delicate flavors. Straining would be done with a linen cloth or fine hair sieve, and bottled in thick glass bottles. Covering with pricked paper rather than cork allowed the syrup to settle and breathe, reducing risk of fermentation before proper sealing. A wooden spoon for stirring and a measuring vessel (probably an earthenware jug marked in pints) completed the toolkit.

Prep Time

15 mins

Cook Time

15 mins

Servings

10

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 2 oz fresh peach blossoms (or if unavailable, substitute with dried peach blossoms or a mix of peach and other edible blossoms such as apple or cherry, 1/3 oz dried = 2 oz fresh)

- 2 cups filtered water

- 4 1/2 cups white caster sugar (double refined, or superfine)

- Paper or muslin cloth for covering bottles

Instructions

- Begin by gathering fresh peach blossoms—about as many as can be densely picked from your tree (roughly 2 oz fresh blossoms per batch).

- Pluck and clean them carefully.

- Place the blossoms in a heatproof bowl, and pour enough filtered water to nearly cover them (about 2 cups per 2 oz blossoms).

- Heat this mixture gently—using a bain-marie (hot water bath) or very low heat—until it is nearly scalding but not boiling (around 175°F).

- Remove from the direct heat, but keep it warm for several hours or overnight (covering helps retain gentle warmth).

- Strain out the blossoms, squeezing gently to extract as much liquid as possible.

- Measure the aromatic infused liquid, and for every 2 cups, add 4 1/2 cups of caster or superfine white sugar.

- Gently warm again, stirring often, until the sugar completely dissolves—do not boil.

- When cool, pour into clean bottles.

- Instead of a tight lid, cover with a perforated paper or cloth tied on, allowing air to escape (for the first few days) before sealing completely for storage.

Estimated Calories

180 per serving

Cooking Estimates

Preparing the blossoms and workspace takes about 15 minutes. Infusing the blossoms with warm water requires about 4 hours, but most of this is hands-off. Cooking just involves gently dissolving the sugar, which takes another 15 minutes. The recipe makes about 10 servings, each with roughly 180 calories from the sugar.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Dietary Preference

Main Ingredients

Culinary Technique

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes