How To Pott Crawfish

From the treasured pages of The Lady Cravens Receipt Book

Written by Elizabeth Craven, Baroness Craven

How To Pott Crawfish

"First boyle your wator well and throw into it a good handfull of salt and then put in your Crawfish which when they are well boyld Shell them and spidt to evdry hundred one quarter of a pound of Butter and what Salt you think convenient with half of Lemmon and soe mash them to gether uppon Coales not to rash then pott them and sett them a Side untill they are Cold and then cover them with Butter that being molted in a Saucer pann over the fire and sett that it may stand till it be Cold before you cover them then you may keep them a Moneth or two or three if you have Occasion not breaking the Butter all topps of them nither doe you neede to cover them at all with any thing"

Note on the Original Text

This recipe, like many of its age, is written in direct, unpunctuated prose, assuming a cook’s familiarity with both the ingredients and the implied steps. Spelling is highly variable—'boyle' for 'boil', 'wator' for 'water', 'spidt' for 'spread' or possibly 'split', and 'pott' for 'pot' (i.e., to preserve in a pot). Quantities are imprecise ('a good handfull of salt'), measurements based on what was intuitive to an experienced cook. Instructions blend processing (boiling, mashing) and preservation (sealing with butter), with practical notes about storage but little commentary on presentation or serving.

Title

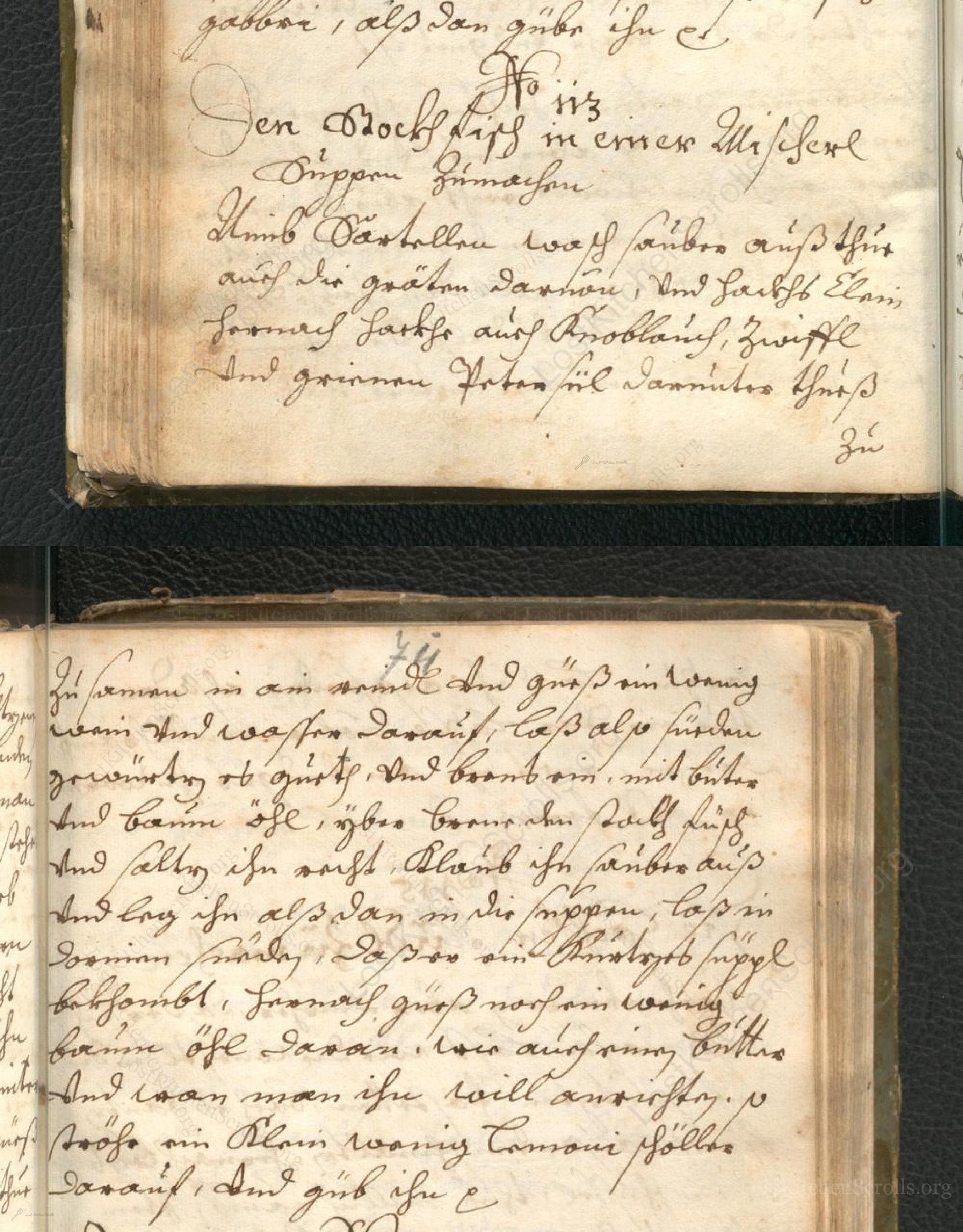

The Lady Cravens Receipt Book (1703)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Elizabeth Craven, Baroness Craven

Era

1703

Publisher

Coome Abbey

Background

A delectable manuscript brimming with 18th-century English delights, Lady Craven's receipt book whisks readers from luscious cakes and puddings to savory feasts and creamy cheeses. Elegantly organized and sprinkled with recipes from an illustrious social circle, this culinary collection offers a sumptuous taste of aristocratic home economics.

Kindly made available by

Penn State University

This recipe comes from Lady Craven's receipt book, compiled in England between 1702 and 1704. At this time, 'potting' was a common preservation technique: sealing cooked foods under butter to exclude air, extending their shelf life in the days before refrigeration. Crawfish, also known as crayfish, were a delicacy found in English rivers and ponds, popular among the aristocracy for feasting and entertaining. Lady Craven’s manuscript is a snapshot of early 18th-century English culinary practice, heavy with French influences and reliant on seasonal, local produce. Recipes often traveled through social circles, each attribution a reflection of networks of women exchanging culinary secrets.

In the early 1700s, the kitchen would have featured a large iron cauldron or copper pot suspended over an open hearth for boiling the crawfish. Long-handled wooden spoons or ladles were used for stirring. The crawfish meat was mashed with a wooden pestle or spoon over hot coals, using heatproof bowls—often stoneware or earthenware. Finished mixtures were packed into ceramic pots or glass jars, covered in melted butter from a small metal saucepan, and set aside to cool in a larder or cool part of the house. No refrigeration was available, so airtight butter seals were the only way to keep potted meats safe for weeks or even months.

Prep Time

25 mins

Cook Time

15 mins

Servings

6

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 2.2 lbs live crawfish (or substitute with crayfish or small lobster tails if unavailable)

- 2-3 quarts water

- 2 oz table salt (plus extra to taste)

- 8 oz unsalted butter (4 oz for mashing, 4 oz for sealing)

- Juice of half a lemon

- Optional: black pepper to taste

Instructions

- Bring 2-3 quarts of water to a brisk boil in a large pot.

- Add a generous handful (about 2 oz) of table salt.

- Add 2.2 lbs live crawfish and boil them until the shells turn bright red and the flesh is cooked through, about 5-7 minutes.

- Allow the crawfish to cool slightly, then remove the shells and place the meat in a bowl.

- For every 100 crawfish tails (approximately 1 lb meat), add 4 oz (one quarter pound) unsalted butter, a pinch or two of salt to taste, and the juice of half a lemon.

- Mash and mix these together gently over low heat (or in a heatproof bowl set over hot coals or low stovetop), just enough to meld the ingredients, not to brown.

- Pack this mixture into sterilized glass jars or ceramic pots.

- Melt additional butter (about 5 oz per jar) in a saucepan and pour it gently to fully cover the crawfish mixture, sealing it from air.

- Let cool completely without disturbing the butter seal; do not cover the jars until fully set.

- Store in a cool place.

- The crawfish, well sealed under butter, will keep refrigerated for up to 2-3 months.

Estimated Calories

360 per serving

Cooking Estimates

We estimate the time to prep, cook, and portion this recipe based on typical steps: boiling and peeling crawfish, mashing with butter, and assembling in jars. Calories are calculated based on butter and crawfish used for a typical serving. This recipe yields about 6 servings.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Dietary Preference

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes