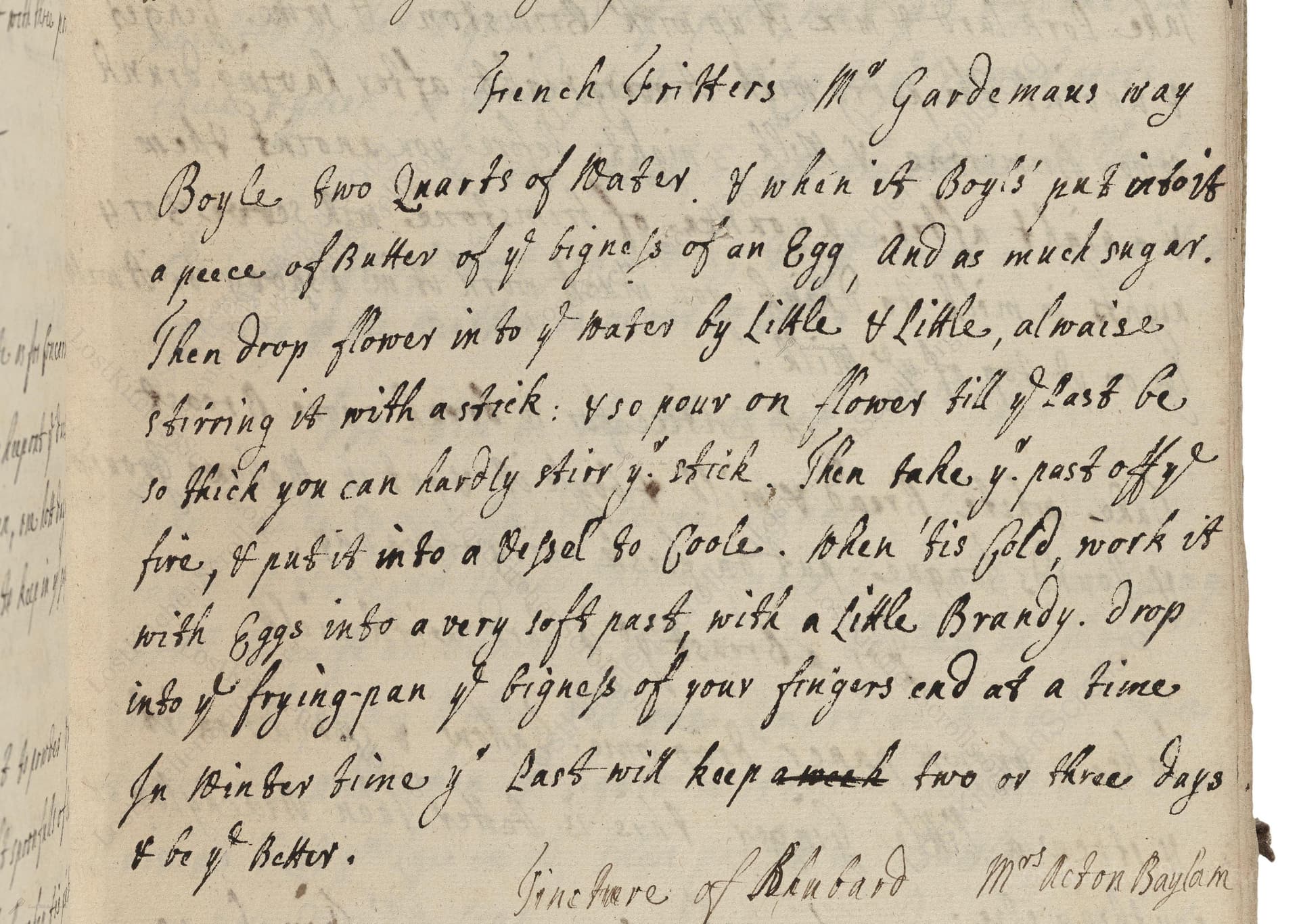

French Fritters Mr Gardemans Way

From the treasured pages of Receipt book of Catherine Bacon

Written by Catherine Bacon

French Fritters Mr Gardemans Way

"Boyle two Quarts of Water. & when it Boyl's' put in sois a peece of Butter of ye bigness of an Egg and as much sugar. Then drop flower in to ye water by little & little, alwaise stirring it with a stick. so pour on flower til ye Past be so thick you can hardly stirr ye stick. Then take ye past off ye fire, & put it into a Vessel to Coole. When 'tis Cold work it with Eggs into a very soft past, with a little Brandy. Drop into ye frying-pan ye bigness of your fingers end at a time. In Winter time ye Past will keep a week two or three Days & be ye better."

Note on the Original Text

This recipe, written in the vernacular of the early 18th century, uses phonetic spelling and period-typical punctuation (e.g., 'Boyle' for boil, 'flower' for flour, 'ye' for the). Directions are given in narrative form, assuming a basic level of kitchen skill from the reader, and measurements are based on familiar objects (like 'the bigness of an egg') rather than precise weights. Ingredients are sometimes listed within the instructions rather than at the top, and the cook is expected to adjust quantities based on tactile cues. Such writing reflects a time before standardization in cookery, relying on tradition, personal judgement, and practical experience.

Title

Receipt book of Catherine Bacon (1730)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Catherine Bacon

Era

1730

Publisher

Unknown

Background

A delightful foray into the kitchens of 17th and early 18th century England, Catherine Bacon’s culinary manuscript offers an elegant medley of recipes and cookery wisdom for the discerning palate of her age.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

This recipe comes from a manuscript attributed to Catherine Bacon, who lived in England from 1660 to 1757. The recipe dates from approximately 1680–1739, an era when household recipe books were handwritten collections of both culinary and medicinal formulas, passed through families and friends. French-style fritters were fashionable at the time, reflecting continental influences at the English table. These fritters are a forerunner to choux pastry-based treats and show how early modern cooks embraced rich, buttery doughs and creative use of alcohol for flavoring.

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, cooks would use large iron or copper pots to boil water over open hearths or coal ranges. A sturdy wooden spoon or stick was essential for stirring starchy doughs. Once mixed, the dough would cool in an earthenware or wooden vessel. Frying was done in a deep cast-iron skillet or pan set over a fire, using rendered animal fats or vegetable oils. Eggs were beaten by hand, and cooks had only their hands and simple utensils to judge dough consistency, making this a hands-on, sensory-driven process.

Prep Time

20 mins

Cook Time

25 mins

Servings

20

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 2 quarts water

- 2 ounces unsalted butter

- 2 ounces granulated sugar

- Approx. 2.5–3.5 cups all-purpose flour

- 3–4 medium eggs (plus extra as needed for soft dough)

- 1 tablespoon brandy

- Oil for frying (sunflower or vegetable oil preferred)

- Extra sugar for dusting (optional)

Instructions

- Begin by bringing 2 quarts of water to a rolling boil in a large saucepan.

- Once boiling, add about 2 ounces of unsalted butter (roughly the size of a medium egg) and 2 ounces of granulated sugar.

- Stir until both have dissolved completely.

- Gradually add all-purpose flour, sprinkling it in a little at a time while constantly stirring with a wooden spoon or heatproof spatula.

- Keep adding flour until the mixture forms a thick dough and is difficult to stir.

- Remove the mixture from the heat and transfer it into a mixing bowl to cool to room temperature.

- Once cooled, beat in eggs, one at a time, until you achieve a soft, almost sticky dough (start with 3–4 medium eggs, adding more if needed).

- Add a small splash (about 1 tablespoon) of brandy to flavor.

- Heat oil in a deep frying pan or pot to 340–355°F.

- Drop spoonfuls of the batter, about the size of your fingertip, into the hot oil.

- Fry until golden brown and swollen, then drain on paper towels.

- Serve warm, dusted with extra sugar if desired.

- In colder weather, the dough can be kept for 2–3 days (up to a week) and is reported to improve with some aging.

Estimated Calories

90 per serving

Cooking Estimates

Preparing the dough takes about 20 minutes, and frying the dough in batches takes another 25 minutes. Each fried piece has about 90 calories, and this recipe makes about 20 servings.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

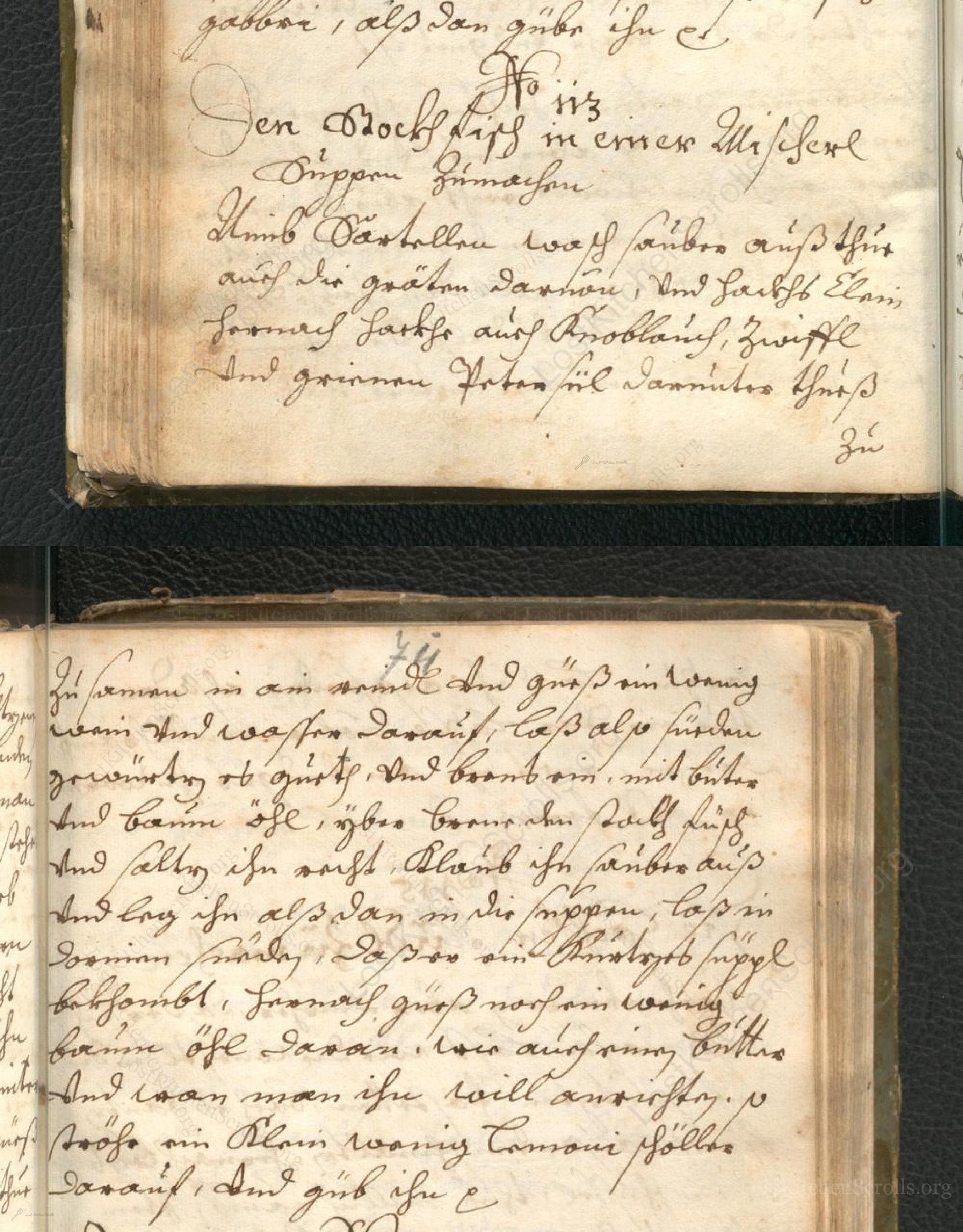

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes