Another Way To Make Sirrup Of Damask-Roses

From the treasured pages of The whole body of cookery dissected

Unknown Author

Another Way To Make Sirrup Of Damask-Roses

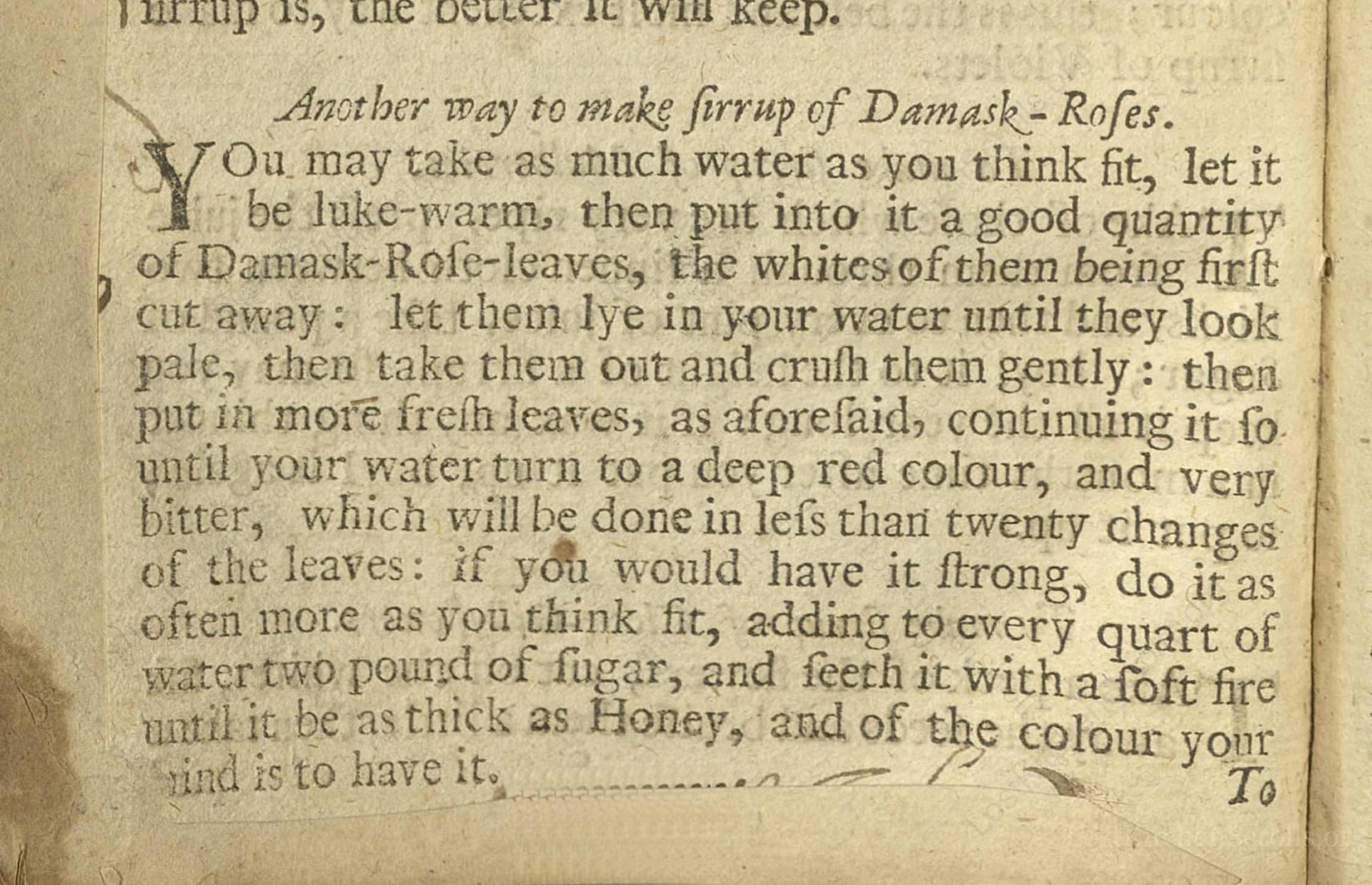

"YOu may take as much water as you think fit, let it be luke-warm, then put into it a good quantity of Damask-Rose-leaves, the whites of them being first cut away: let them lye in your water until they look pale, then take them out and crush them gently: then put in more fresh leaves, as aforesaid, continuing it so until your water turn to a deep red colour, and very bitter, which will be done in less than twenty changes of the leaves: if you would have it strong, do it as often more as you think fit, adding to every quart of water two pound of sugar, and seeth it with a soft fire until it be as thick as Honey, and of the colour your mind is to have it."

Note on the Original Text

The recipe is written in a straightforward, almost conversational manner, typical of 17th-century English cookery books. Quantities are imprecise—'as much water as you think fit'—since cooks were expected to rely on experience and context. Directions are iterative: repeating the petal infusion 'twenty' times speaks to color and strength rather than precise measurement. Unfamiliar spellings (like 'sirrup' for syrup, 'seeth' for boil/heat, and 'lye' for lie/sit) are due to the early modern English in use at the time. The cook is clearly trusted to exercise judgment about color, thickness, and flavor, reflecting the hands-on, apprenticeship approach to kitchen learning in the past.

Title

The whole body of cookery dissected (1673)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Unknown

Era

1673

Publisher

Unknown

Background

A sumptuous exploration of 17th-century English cookery, 'The whole body of cookery dissected' serves up an array of recipes and kitchen wisdom, offering a flavorful journey through the dining tables of Restoration England.

Kindly made available by

Texas Woman's University

This recipe is drawn from 'The whole body of cookery dissected', first published in 1673, a period of great interest in preserves, conserves, and sweetmeats. Rose syrups—made from highly prized Damask roses—were cherished both for their luxurious aroma and their supposed medicinal properties. They were common in upper-class English households, used not only as a sweetener or cordial but also as a genteel demonstration of refinement and wealth. Such syrups might brighten up a cordial, flavor a dessert, or simply delight guests with their intense floral taste. In 17th-century England, cooks worked seasonally, making such flower syrups when blossoms were at their peak. Sugar was expensive, so these recipes speak to the status of households that could afford them.

Back in the 17th century, this syrup would have been made using earthenware or copper pans set over a hearth or open fire, with cooks controlling the heat as best they could. Petals would be steeped in bowls or basins, likely of ceramic, and then strained and pressed through cloths or sieves. Ladles and wooden spoons were used to stir the syrup gently. For storage, the finished syrup would be poured into glass bottles or stoneware jugs and sealed, sometimes with pig bladders or parchment tied with string—far from the airtight bottles we use today.

Prep Time

1 hr 30 mins

Cook Time

15 mins

Servings

20

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 1 quart lukewarm water

- A large quantity (approximately 2–3 pounds) fresh Damask rose petals (or other highly fragrant rose petals, with white base removed)

- 4 1/4 pounds granulated sugar (per quart of rose infusion)

Instructions

- Begin by choosing the amount of water you desire – for a manageable amount, let’s use 1 quart of water.

- Warm this water to a gentle, lukewarm temperature (about 104°F).

- Remove the white base from fresh Damask rose petals (or any fragrant garden rose, if Damask roses are unavailable), and place a generous handful into the warm water.

- Let the petals steep until they lose their vibrant color and appear pale.

- Remove the spent petals, gently pressing them to extract their color and essence, then discard them.

- Add new fresh petals to the same water, repeating the process—changing out the petals up to 20 times, or until the water becomes a rich, deep pink-red and takes on a slight bitterness.

- For a more intense syrup, you can repeat the petal infusion additional times as desired.

- Once you're satisfied with the color and flavor, measure the water and for each quart, add approximately 4.25 pounds of sugar (keeping the traditional heavy sweetness).

- Gently heat the mixture over low heat, stirring frequently, until it thickens to a syrupy consistency, similar to liquid honey.

- Allow to cool, then bottle and store.

Estimated Calories

200 per serving

Cooking Estimates

You will spend most of your time steeping rose petals in warm water and replacing them until you reach a deep color. Cooking the syrup is quite fast but infusing the petals takes longer. The calories mainly come from the sugar used to make the syrup. This recipe makes enough syrup for about 20 servings.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Dietary Preference

Culinary Technique

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes