Chilaquiles

"Chilaquiles"

From the treasured pages of La Cosina en el Bolsillo No. 4

Written by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo; José Guadalupe Posada

Chilaquiles

"Para que salgan buenos deben emplear-se las tortillas frías, pues calientes del co-mal se deshacen al hervir formando una masa desagradable a la vista y al paladar. Se parten las tortillas en pedazos, ni muy grandes ni muy pequeños, se fríen en bas-tante manteca hasta que se doren y luego se sacan. Si van a ser en tomate, se asan éstos, pues así tienen mejor gusto que co-cidos; se muelen con ajo y chiles verdes al gusto y se echan a freir. Cuando esté bien refrito el tomate, se le agrega el agüa nece-saria y la sal suficiente, dejándolo hervir un rato muy corto, en seguida se echan ahí los pedazos de tortilla fritos y se dejan sa-zonar; al quitarlos de la lumbre se les po-nen trozos de carne de puerco frita, longa-niza, frita también, cebolla picada, y queso añejo. Si son en gitomate, se procede del mismo modo que con los tomates y si son de chile colorado, se emplean el mulato y el pasilla, desvenados, tostados, molidos y fritos como queda dicho."

English Translation

"CHILAQUILES. To make them turn out well you must use cold tortillas, because if they are warm from the griddle they fall apart while boiling and form a mass that is unpleasant to the eye and to the palate. Cut the tortillas into pieces, not too large nor too small, and fry them in plenty of lard until golden, then remove them. If you are making them with tomatoes, roast the tomatoes, as this gives them a better flavor than boiling; grind them with garlic and green chilies to taste and add them to the hot oil to fry. When the tomato is well fried, add the necessary water and enough salt, letting it boil for just a short while, then add the fried tortilla pieces and let them season; when removing from the heat, add pieces of fried pork, fried chorizo as well, chopped onion, and aged cheese. If you are making them with gitomate (red tomatoes), proceed the same way as with the regular tomatoes, and if you are making them with red chile, use mulato and pasilla chiles, seeded, toasted, ground, and fried as previously described."

Note on the Original Text

The recipe is written in the instructive, narrative style of early-20th-century Mexican domestic guides, focused more on method than on precise measurements—assuming a common-sense cook in the kitchen familiar with staples and tools. Spelling reflects the orthographic conventions of the era (for example, 'co-mal' for comal, 'mant-e-ca' for manteca, 'gitomate' for tomatillo/green tomato), and the fluid blending of indigenous Nahuatl words into everyday Spanish. Directions are meditative, often suggesting variations according to available ingredients, inviting improvisation and local adjustment.

Title

La Cosina en el Bolsillo No. 4 (1913)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Antonio Vanegas Arroyo; José Guadalupe Posada

Era

1913

Publisher

Unknown

Background

Part of the delightful 'Cocina en el bolsillo' series, this charming 1913 cookbook serves up a pocket-sized collection of tempting recipes for a variety of dishes, perfect for culinary explorers of all kinds.

Kindly made available by

University of Texas at San Antonio

This chilaquiles recipe appeared in 'La Cosina en el Bolsillo No. 4,' published in 1913 by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, with illustrations by José Guadalupe Posada. The little booklet is part of a larger series designed for home cooks in early 20th-century Mexico. At the time, recipes were crafted for practical, economical family cooking, making use of staple ingredients like tortillas and leftover meats. Chilaquiles, originally a thrifty dish for repurposing stale tortillas, became a beloved breakfast across Mexican households—layered with indigenous traditions and Spanish influences, and often tailored to what was at hand. This recipe reflects early-20th-century ingenuity, blending simplicity with robust flavor, and highlights Mexico's rural kitchen techniques just as urbanization and mass publishing began sharing such home tricks beyond single families.

Historically, the tortillas would be fried in a heavy pozo (cauldron or deep pan) over a wood or charcoal-fired comal or standard cook fire. A stone molcajete (mortar and pestle) would be used to grind the roasted tomatoes, garlic, and chiles, imparting a texture and subtle mineral flavor. Sauces were fried in cast iron or clay cazuelas on the stovetop. Metal or hand-carved wooden spatulas helped stir the tortillas and sauce. Plates or shallow clay cazuelas served as both the mixing and serving vessels, while cheese was often broken up by hand.

Prep Time

20 mins

Cook Time

25 mins

Servings

4

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 12 cold corn tortillas (about 10.5 oz)

- 1 cup neutral oil or lard for frying

- 4 large ripe tomatoes (about 1.3 lb) or 8-10 tomatillos (for gitomate version)

- 2–3 cloves garlic

- 2–4 fresh green chiles (jalapeño or serrano), or 3–4 dried mulato or pasilla chiles (for chile colorado version)

- 1 1/4 cups water

- Salt, to taste

- 7 oz pork shoulder or belly, cut into chunks and fried

- 3.5 oz longaniza or Mexican chorizo, sliced and fried

- 1/2 medium white onion, finely chopped

- 3–3.5 oz Cotija or other aged Mexican cheese, crumbled

Instructions

- To recreate these historical chilaquiles, begin with about 12 cold corn tortillas—day-old tortillas are best, as fresh ones will disintegrate into an unappetizing mush.

- Cut the tortillas into medium-sized pieces, not too large and not too small.

- Fry them in about 1 cup of neutral oil or lard (manteca) until golden and crisp, then remove and drain.

- For the sauce, char (roast) 4 large ripe tomatoes over a flame or in a dry skillet until their skins blister, as this enhances their flavor over simply boiling.

- Blend the roasted tomatoes with 2–3 cloves of garlic and 2–4 fresh green chiles (jalapeño or serrano—adjust to your heat preference).

- Fry the sauce in a pan with a touch of oil until well-reduced and aromatic, then add about 1 1/4 cups water and salt to taste.

- Bring to a gentle simmer for just a minute.

- Add the crispy tortilla pieces to the sauce and let them briefly soak and heat through—just to coat and soften slightly, but not long enough to lose their crunch.

- Off the heat, top with chunks of fried pork (about 7 ounces), slices of fried longaniza or Mexican chorizo (about 3.5 ounces), finely chopped onion (1/2 medium), and a generous sprinkle (about 3–3.5 ounces) of crumbled aged cheese like Cotija.

- If you wish to use tomatillos instead of red tomatoes (as in 'gitomate'), simply substitute the tomatoes with 8–10 tomatillos, roasted and blended in the same way.

- For a red chile version, use 3–4 dried mulato or pasilla chiles—stemmed, seeded, toasted lightly, then blended and fried as for the tomato sauce.

Estimated Calories

550 per serving

Cooking Estimates

It usually takes about 20 minutes to get all the ingredients ready, then about 25 minutes to cook everything. This recipe makes 4 hearty servings, and each serving is about 550 calories.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Dietary Preference

Main Ingredients

Occasions

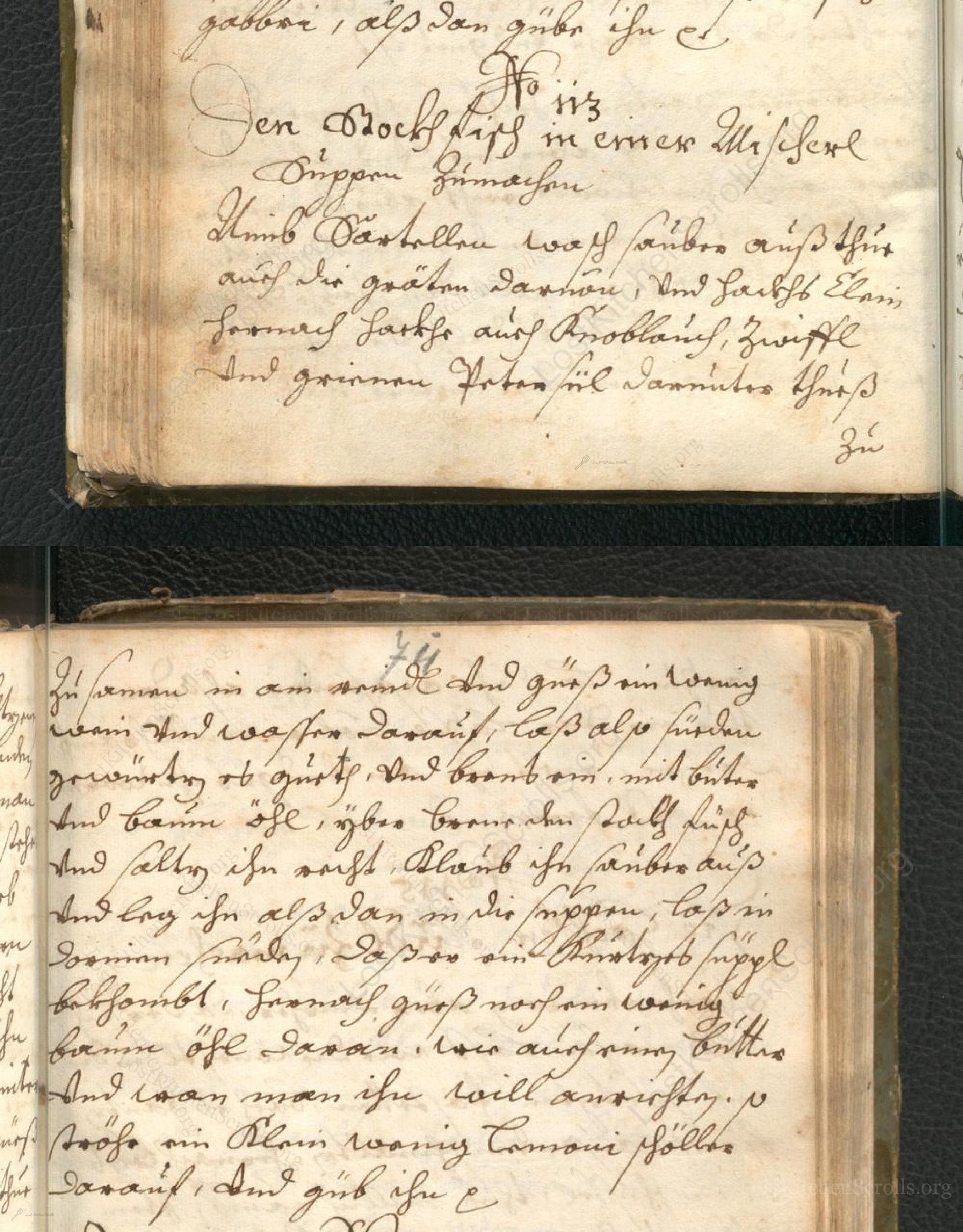

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Recht Guts Latwerg

This recipe hails from a late 17th-century German manuscript, a comprehensive co...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes