The Best Way To Salt A Gamon

From the treasured pages of Medicinal, household and cookery receipts 1600s

Unknown Author

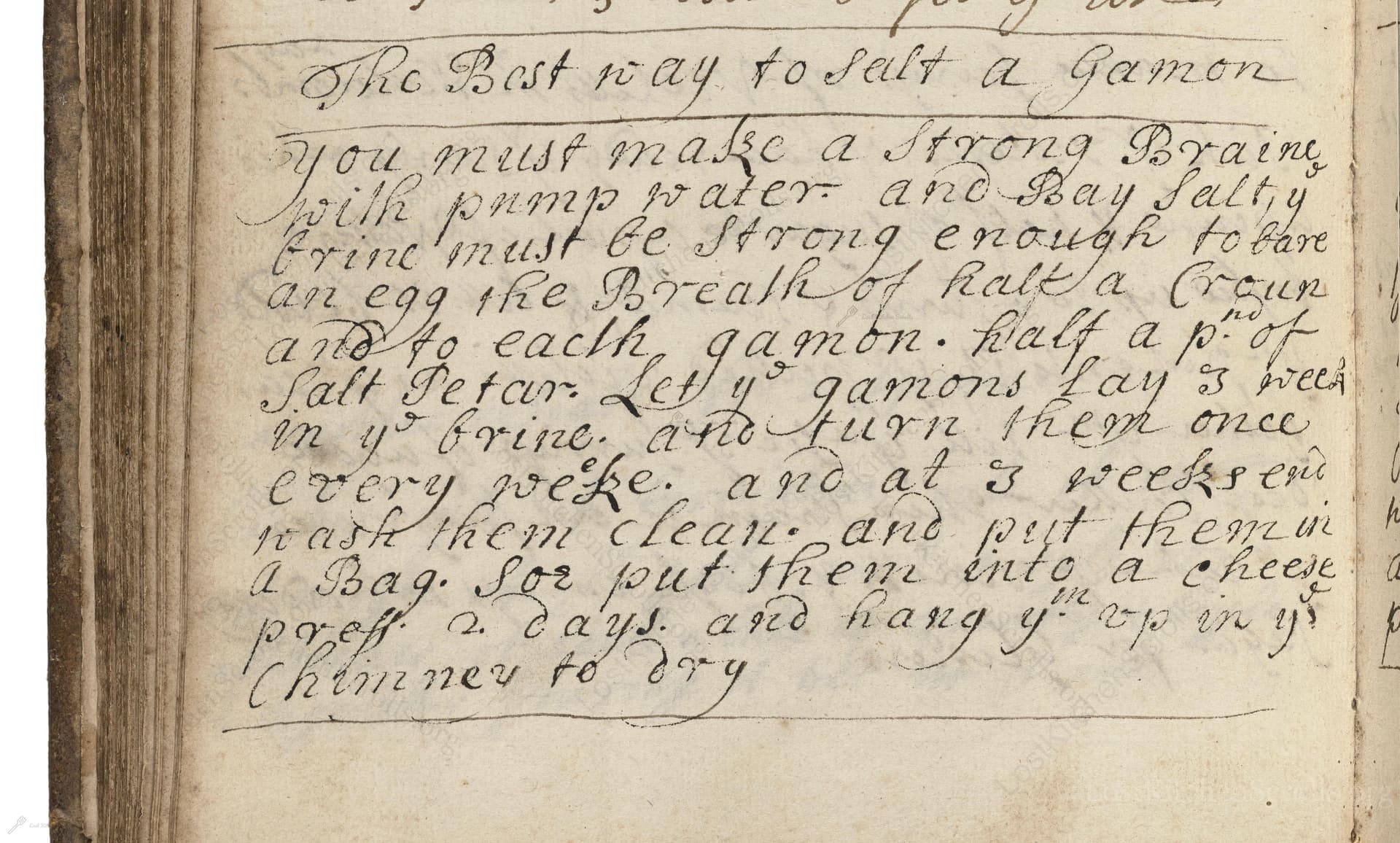

The Best Way To Salt A Gamon

"You must make a strong Braine with pump water and Bay Salt, ye brine must be strong enough to bare an egg the Breath of half a Crown and to each gamon. half a pd of Salt Petar. Let ye gamons lay 3 week in ye brine. and turn them once every weeke. and at 3 weeks end wash them clean. and put them in a Bag. Soe put them into a cheese press 2 days. and hang ym up in ye Chimney to dry"

Note on the Original Text

The original recipe is written with charming period spelling and abbreviations like 'ye' (for 'the') and 'ym' (for 'them'). Measures like 'the Breath of half a Crown' guided cooks to judge brine strength by sight and touch, not numbers—this underscores the tactile approach of past cooks. Recipes were often terse, intended as reminders for those already familiar with the basics of salting and preserving; punctuation is sparse and instructions assume a degree of prior experience with the kitchen tools and methods of the day.

Title

Medicinal, household and cookery receipts 1600s (1650)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Unknown

Era

1650

Publisher

Unknown

Background

A delightful glimpse into the kitchens of the 17th century, this historical culinary gem serves up a feast of recipes and gastronomic secrets that will tantalize any food lover’s curiosity.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

This recipe hails from the 1600s to 1700s, a period when salting was the primary method for preserving meat through the long winter months. Large joints of pork, especially the prized gammon, were salted after the autumn slaughter to provide food into spring. Bay salt, harvested from salt flats and shipped from the Bay of Biscay, was considered superior to common salt for preservation. The described process reflects the homely ingenuity of early modern English households, combining science (saltpetre’s preservative qualities) with everyday practicality. Hanging meat in the chimney to dry not only cured it but subtly flavored it with woodsmoke—a flavor synonymous with country kitchens of the era.

Back in the day, the key tools included a large brining tub or barrel, a wooden ladle or stirring stick to mix the brine, and a simple egg for density testing. A heavy stoneware cheese press, or a wooden press weighted with stones, was used to expel moisture. Strong cloth or linen bags cradled the gammon during pressing and hanging. Finally, the kitchen hearth or chimney, with its constant airflow, served as the traditional place for drying meats.

Prep Time

30 mins

Cook Time

0 mins

Servings

30

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 1 1/3 gallons cold filtered or mineral water

- 3 3/4 lbs bay salt (substitute: coarse sea salt, if bay salt unavailable)

- 1 fresh egg (for testing brine strength)

- 1 large gammon (uncured hind leg of pork, approx. 18-20 lbs)

- 8 ounces saltpetre (potassium nitrate; available from specialist suppliers)

- Muslin or cotton bag

Instructions

- Begin by making a strong brine with cold water (ideally filtered or mineral), and bay salt (otherwise use coarse sea salt).

- The brine should be salty enough to float a fresh egg—the density can be checked by placing a clean egg in the brine; it should lift and partially break the surface, around the width of a modern 2-euro coin (about 1 inch).

- For each gammon (a cured hind leg of pork, or substitute with a large pork leg), add about 8 ounces of saltpetre (potassium nitrate).

- Completely submerge the gammon in the brine for 3 weeks in a cool place, turning it once every week.

- After three weeks, remove the meat, rinse it thoroughly, then place it in a cloth bag.

- Press it in a cheese press (or use heavy weights atop the wrapped meat) for 2 days to remove excess moisture.

- Finally, hang the gammon in a dry, well-ventilated place—traditionally, above the kitchen fire or in the chimney—to air-dry before use.

Estimated Calories

450 per serving

Cooking Estimates

It takes just a few minutes to prepare the brine and the meat, but the main time is spent waiting: three weeks to brine the gammon, two days to press out moisture, and extra time to air-dry before use. There is no actual cooking needed until you want to use the gammon in a recipe.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Dietary Preference

Main Ingredients

Occasions

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes