To Make Vinegar

From the treasured pages of Cookbook of Elizabeth Langley

Written by Elizabeth Langley

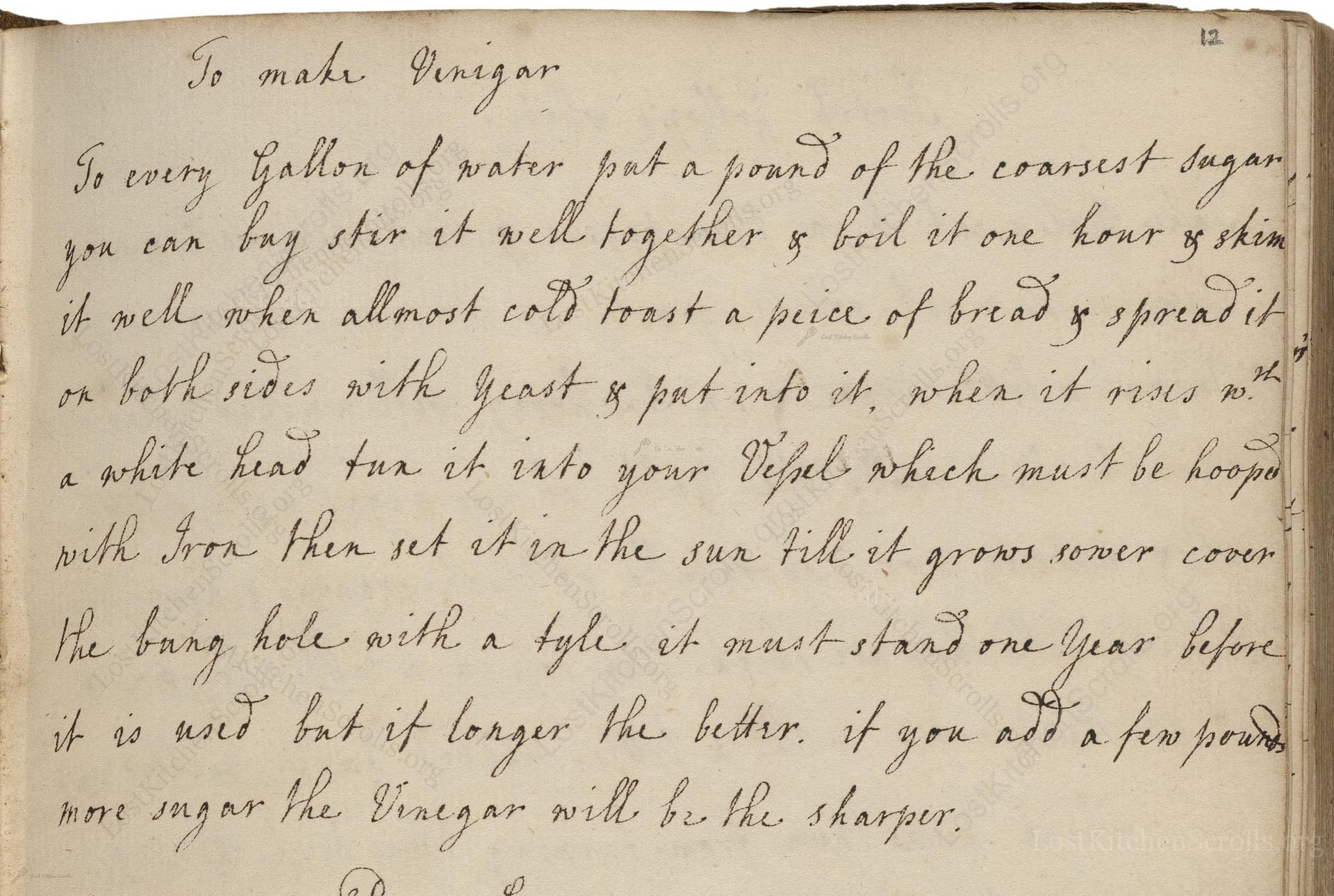

To Make Vinegar

"To every Gallon of water put a pound of the coarsest sugar you can buy stir it well together & boil it one hour & skim it well when allmost cold toast a piece of bread & spread it on both sides with Yeast & put into it, when it rises with a white head tun it into your Vessel which must be hoop'd with Iron then set it in the sun till it grows cover over the bang hole with a tyle it must stand one Year before it is used but if longer the better. if you add a few pound more sugar the Vinegar will be the sharper."

Note on the Original Text

The recipe is written in the informal, conversational style typical of domestic manuscripts from the mid-18th century: measurements are given by volume and weight, and instructions depend on kitchen intuition rather than precise timing or temperature. Words like 'Gallons' and 'pounds' refer to British imperial units. 'Yeast' would have been a wet, bready paste from brewing or baking, not the granulated packets we use today. Archaic spellings like 'hoop'd', 'tyle', and 'used but if longer the better' reflect both regional dialect and the casual, unstandardized orthography of Georgian England. 'Tun it into your vessel' means to pour the fermenting vinegar base into its barrel or jar. The note about additional sugar affirms the direct relationship between sugar quantity and acidity.

Title

Cookbook of Elizabeth Langley (1757)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Elizabeth Langley

Era

1757

Publisher

Unknown

Background

Step into the Georgian kitchen with Elizabeth Langley's 1757 culinary collection, where refined techniques and delightful recipes await those with a taste for historic gastronomy.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

This recipe hails from the mid-18th century, attributed to Elizabeth Langley, who was active in 1757. Vinegar-making was both a household necessity and a clever way to preserve surplus produce or flavor dishes when lemons and other acids were scarce. Sugar was still a luxury, but by this date, even coarser grades were available to the wider public. Homemade vinegar was not just for culinary use; it served medicinal and cleaning purposes, reflecting the thrifty, multi-functional nature of early modern English kitchens. Langley’s instructions paint a vivid picture of domestic alchemy, as women in well-equipped homes converted staples—bread, sugar, and yeast—into versatile pantry acids over the course of many months.

The original cook would have used a large iron or copper cauldron for boiling the water and sugar. Skimming was done with a broad wooden or metal spoon. The fermentation vessel would have been a wooden barrel tightly hooped with iron bands, or a large ceramic or stoneware jar, both robust enough to withstand a year or more of standing fermentation. The bread was likely toasted over an open hearth, and baker’s yeast would have come from the local bakeshop. A flat ceramic tile or plate would cover the barrel’s opening (the 'bang hole'), allowing airflow but blocking debris, weeds, and insects. A sunny spot—such as a south-facing window or garden wall—helped warm the mixture and encourage fermentation.

Prep Time

10 mins

Cook Time

1 hr

Servings

130

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 1 gallon (4 quarts) water

- 1 pound (16 ounces) coarse brown or muscovado sugar (substitute with molasses or dark brown sugar if needed)

- 1 thick slice of rustic bread (white or wholemeal)

- fresh yeast (0.5–0.7 ounces [15–20 grams], or use active dry yeast as a substitute)

- additional 2–4 pounds sugar for stronger vinegar (optional)

Instructions

- To make this early English vinegar at home, take 1 gallon (4 quarts) of water and add 1 pound (16 ounces) of the darkest, least refined cane sugar you can find—think of either raw muscovado sugar or even treacle for a deeper flavor.

- Stir thoroughly, bring to a boil, and simmer for one hour, skimming off any scum that rises.

- Once cooled to warm (not hot), toast a thick slice of rustic bread.

- Generously spread fresh baker’s yeast on both sides of the toast, then float the bread in the cooled sugary water.

- Allow the mixture to rest uncovered until it begins to ferment and froth with a white head.

- When this occurs, pour everything, including the bread, into a sanitized glass or ceramic vessel (traditionally with an iron-hooped barrel) and cover the opening with a ceramic tile or plate, leaving it slightly ajar to allow air flow.

- Place in a sunny spot for at least one year before using; longer aging will yield a sharper vinegar.

- For a stronger vinegar, add 2–4 extra pounds of sugar at the start.

Estimated Calories

45 per serving

Cooking Estimates

It takes about 10 minutes to get your ingredients and tools ready, plus 1 hour to simmer the mixture. The vinegar ferments for at least 1 year before it's ready. If you divide the total vinegar made into servings of about 30 ml (2 tablespoons), each serving has around 45 calories.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Dietary Preference

Main Ingredients

Occasions

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes