To Make Cracknels

From the treasured pages of The Lady Grace Castleton's booke of receipts

Written by Grace Saunderson, Viscountess Castleton

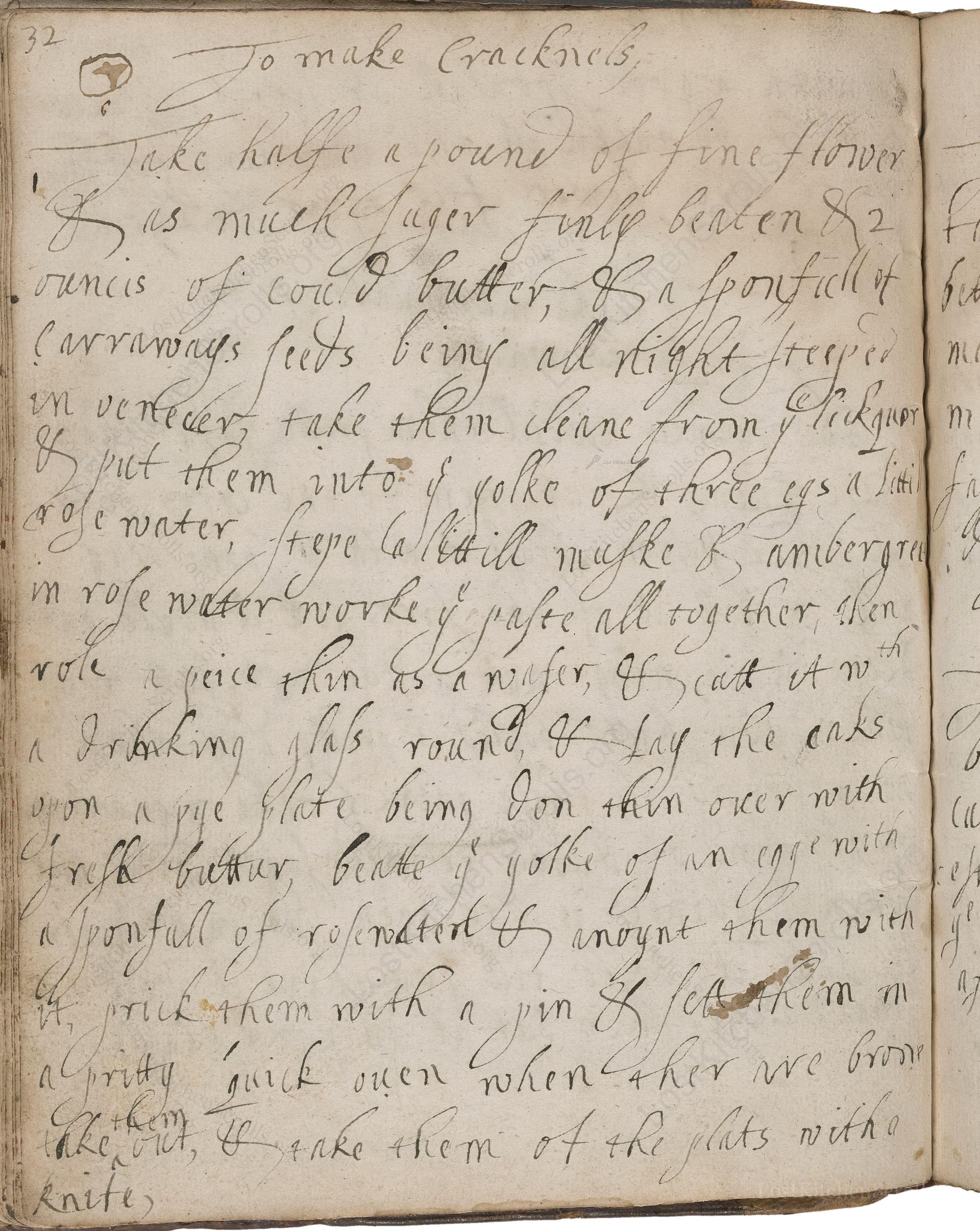

To Make Cracknels

"Take halfe a pound of fine flower as much suger finely beaten & 2 ouncis of cold butterr, & a sponfull of carraways feeds being all night steeped in verjuice, take them cleane from ye lickquor & put them into ye yolke of three egs a litle rose water, stepe litle muske & amber gresse in rose water, worke ye paste all together, then role a peice thin as a wafer, & cutt it with a Drinking glass round, & Lay the caks upon a pye plate, being don thin ouer with fresh butterr, beate ye yolke of an egge with a sponfull of rosewater, & anoynt them with it, prick them with a pin & set them in a pritty quick ouen when they are brown take them out, & take them of the plats with a knife,"

Note on the Original Text

The original recipe is written in the typical concise, functional style of early modern English manuscript cookery. Spellings are phonetic and variable ('flower' for flour, 'ouer' for over, 'lickquor' for liquor), punctuation is sparse, and steps are bundled together—assuming the cook's domestic competency. Recipes often reference rare ingredients (like musk and ambergris) without concern for modern sourcing or safety; these were aromatic status symbols rather than everyday fare. Quantities are given liberally, with references like 'a sponfull' or 'as much suger as flower,' leaving precise measurements to the reader's experience.

Title

The Lady Grace Castleton's booke of receipts (1650)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Grace Saunderson, Viscountess Castleton

Era

1650

Publisher

Unknown

Background

A delightful voyage into 17th-century English kitchens, this collection reveals the refined tastes and culinary secrets of the aristocracy, serving up a sumptuous array of period recipes and gracious domestic wisdom.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

This recipe for cracknels comes from the handwritten household book of Grace Saunderson, Viscountess Castleton, who lived during the mid to late 1600s. The collection is a testament to the culinary sophistication of the English gentry. Cracknels were a popular sweet—delicate, crisp biscuits, almost wafer-thin, perfumed with rose water and occasionally enriched with exotic aromatics like musk and ambergris, reflective of wealth and global trade. In a world without modern leaveners or convenience foods, cracknels were both a treat and a showcase of domestic skill: their finely wrought texture and aroma marked them as special-occasion fare.

In the 17th century, dough would have been mixed in a large wooden bowl, the butter cut in by hand or with a knife. The thin sheets required a rolling pin (often wooden and unmeasured), and rounds could be cut using a drinking glass, as specified. Baking was likely done on flat iron or pewter pie plates within a wood-fired oven, managed for a 'pretty quick' (hot) heat. Brushing was done with a feather or pastry brush, and the pinpricks made with an actual sewing pin. Finished cracknels were carefully lifted off the plates using a broad knife.

Prep Time

35 mins

Cook Time

15 mins

Servings

20

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 8 oz plain flour

- 8 oz caster sugar

- 2 oz unsalted butter, cold

- 1 tablespoon (1/3 oz) caraway seeds

- 2 tablespoons (2 fl oz) verjuice (or diluted white wine vinegar)

- 3 medium egg yolks

- 1 tablespoon (1/2 fl oz) rose water, plus more for brushing

- Pinch of musk (substitute: drop of vanilla extract)

- Pinch of ambergris (substitute: omit or use additional vanilla)

- 1 additional egg yolk (for glazing)

- Extra melted butter (for brushing)

Instructions

- To recreate 17th-century cracknels in your modern kitchen, begin with 8 oz of finely milled plain flour and 8 oz of caster sugar.

- Rub in 2 oz of cold unsalted butter until you achieve fine crumbs.

- Steep 1 tablespoon (about 1/3 oz) of caraway seeds in 2 tablespoons (2 fl oz) of verjuice (unripe grape juice or substitute with diluted white wine vinegar) overnight.

- The next day, drain the seeds and discard the liquid.

- Beat in the yolks of 3 medium eggs along with 1 tablespoon (1/2 fl oz) of rose water.

- Optional: If available, steep a pinch of musk and ambergris (rare and not typically edible today—substitute with a hint of vanilla extract to capture an aromatic touch) in additional rose water and add to the dough.

- Mix all together to form a soft, cohesive paste.

- Roll the dough out very thin—like a wafer—on a floured surface.

- Cut rounds with a small glass and lay them on a baking sheet.

- Brush the tops thinly with melted butter.

- Beat an extra egg yolk with a tablespoon of rose water and brush this mixture over the rounds.

- Prick each with a pin, then bake in a hot oven (400°F) until golden brown.

- Remove with a palette knife to cool.

Estimated Calories

90 per serving

Cooking Estimates

You will need to soak the caraway seeds overnight, prepare and roll out the dough, and bake the cracknels until they turn golden brown. Prep includes mixing, rolling, and cutting out the dough, while baking is the actual cook time. Each serving is one cracknel, and calories are estimated per piece.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

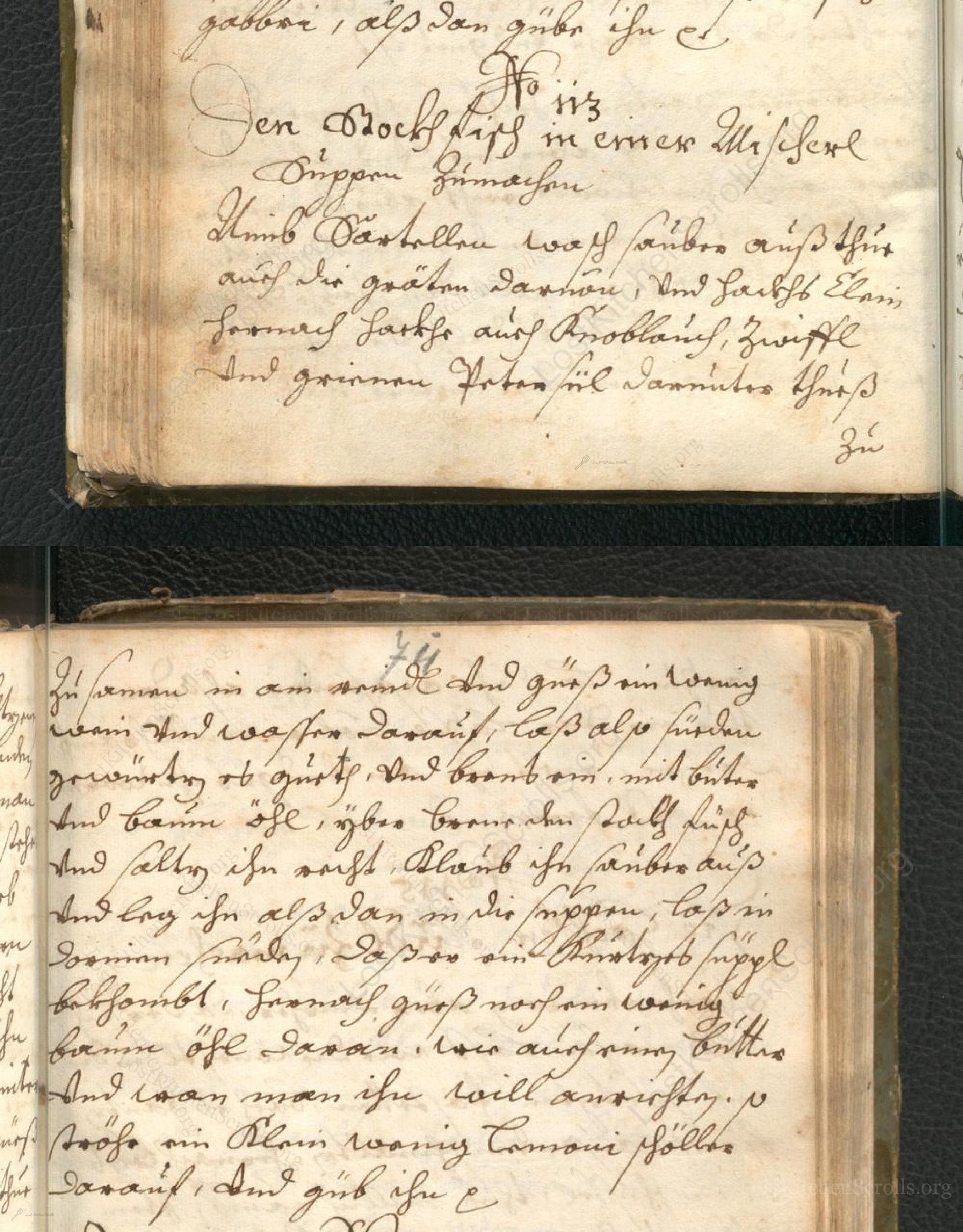

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes