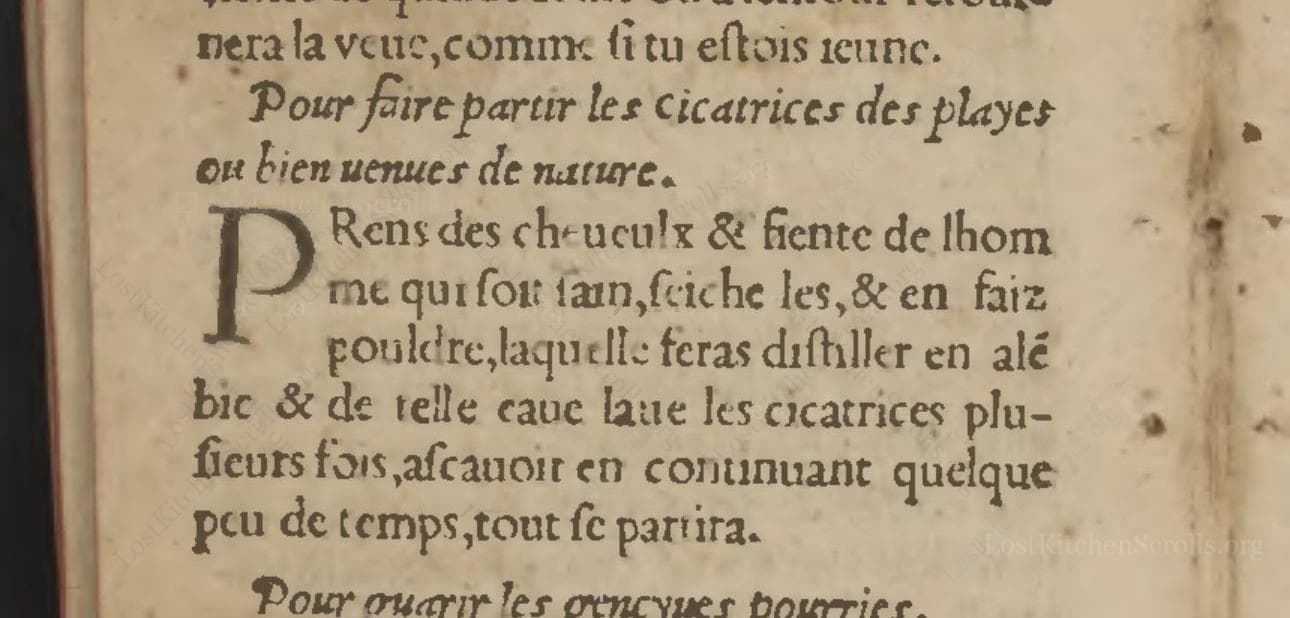

Pour Faire Partir Les Cicatrices Des Playes Ou Bien Venues De Nature

"To Remove Scars From Wounds Or Those That Have Appeared Naturally"

From the treasured pages of Bastiment de receptes

Unknown Author

Pour Faire Partir Les Cicatrices Des Playes Ou Bien Venues De Nature

"Prens des cheueulx & fiente de lhom me qui soit sain, feiche les, & en faiz pouldre, laquelle feras distiller en ale bic & de telle eaue laue les cicatrices plusieurs fois, afcauoir en continuant quelque peu de temps, tout se partira."

English Translation

"To remove scars from wounds or those that have appeared naturally. Take the hair and dung of a healthy man, dry them, and make them into powder. Distill this in alembic, and with such water, wash the scars several times; by continuing for some time, all will disappear."

Note on the Original Text

The original recipe is written in early modern French, where spelling is inconsistent by modern standards ('cheueulx' for 'cheveux' (hair), 'lhom me' for 'l'homme', and 'fiente' for feces). 'Distiller' here doesn't always mean literal distillation but sometimes simply to steep or infuse. Recipes of this era were concise and relied upon the reader's understanding of contemporary techniques and the availability of home tools. Measurements were rarely given, with proportions implied by familiarity or practical logic rather than exact science.

Title

Bastiment de receptes (1541)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Unknown

Era

1541

Publisher

A Lescu de Coloigne

Background

Step into the culinary secrets of Renaissance France! 'Bastiment de receptes' is a delectable compendium newly translated from Italian, brimming with recipes, curious odors, and medicinal tidbits designed to both delight the palate and preserve health.

Kindly made available by

Library of Congress

This recipe hails from the mid-16th century French text 'Bastiment de receptes' (1541), a book that straddles the worlds of early home remedies and secrets of health, beauty, and scent. Printed in Lyon during a Renaissance boom in both literacy and curiosity about the natural world, it blends Italian know-how with local traditions. At the time, medical and cosmetic advice drew upon Galenic principles of humors and material correspondences. Ingredients common to the body—hair, feces—were believed to have power to heal or balance maladies visible on the skin, like scars and birthmarks. These books were meant for literate households, blending folk tradition and the professional world of apothecaries.

Period practitioners would use a mortar and pestle to grind and mix the dried ingredients. Distillation in the 16th century might mean using a simple alembic still, or more likely, just infusing or steeping the powder in ale and straining through a coarse cloth or hair sieve. Application was made with linen cloths or sponges, gently dabbing the treated area multiple times daily. Ale itself was commonly brewed at home or acquired from local taverns, and households would have both glass and ceramic vessels suitable for both distillation and infusion.

Prep Time

15 mins

Cook Time

0 mins

Servings

1

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 0.18 ounces clean, healthy human hair (or substitute with animal hair, e.g., horsehair, if required for safety)

- 0.18 ounces dried, sterilized animal manure (e.g., composted cow manure; never use fresh or human feces for safety reasons)

- 3.4 fluid ounces strong ale (6–8% ABV, unflavored for neutrality)

Instructions

- To replicate this intriguing old recipe today, start by finding human hair—yes, from a healthy person—and a small amount of dried human feces (a substitute like safe, sterilized animal manure, e.g., composted cow manure, could be used as a non-harmful alternative; do not use real human feces for any medical application!).

- Blend together equal parts, about 0.18 ounces each.

- Dry them thoroughly and grind to a fine powder.

- This powder would then be distilled—in the historical sense, likely meaning mixed into ale and allowed to settle, or possibly heated with ale to extract any soluble elements.

- Modernly, infuse the powder in about 3.4 fluid ounces of strong ale, stir, and strain.

- Use the resulting liquid (filtered 'wash') to bathe scars or skin blemishes multiple times per day, over several days.

- This was not for ingestion but for topical application.

- Naturally, this remedy is not medically endorsed today, but it gives a glimpse into early modern approaches to skin care!:

Estimated Calories

2 per serving

Cooking Estimates

This recipe takes about 5 minutes to gather and prepare the ingredients, and an additional 10 minutes to infuse and strain the mixture. There is no actual cooking involved. Since this is for topical use and not ingestion, it has minimal calories. The recipe produces enough liquid for approximately 1 application.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

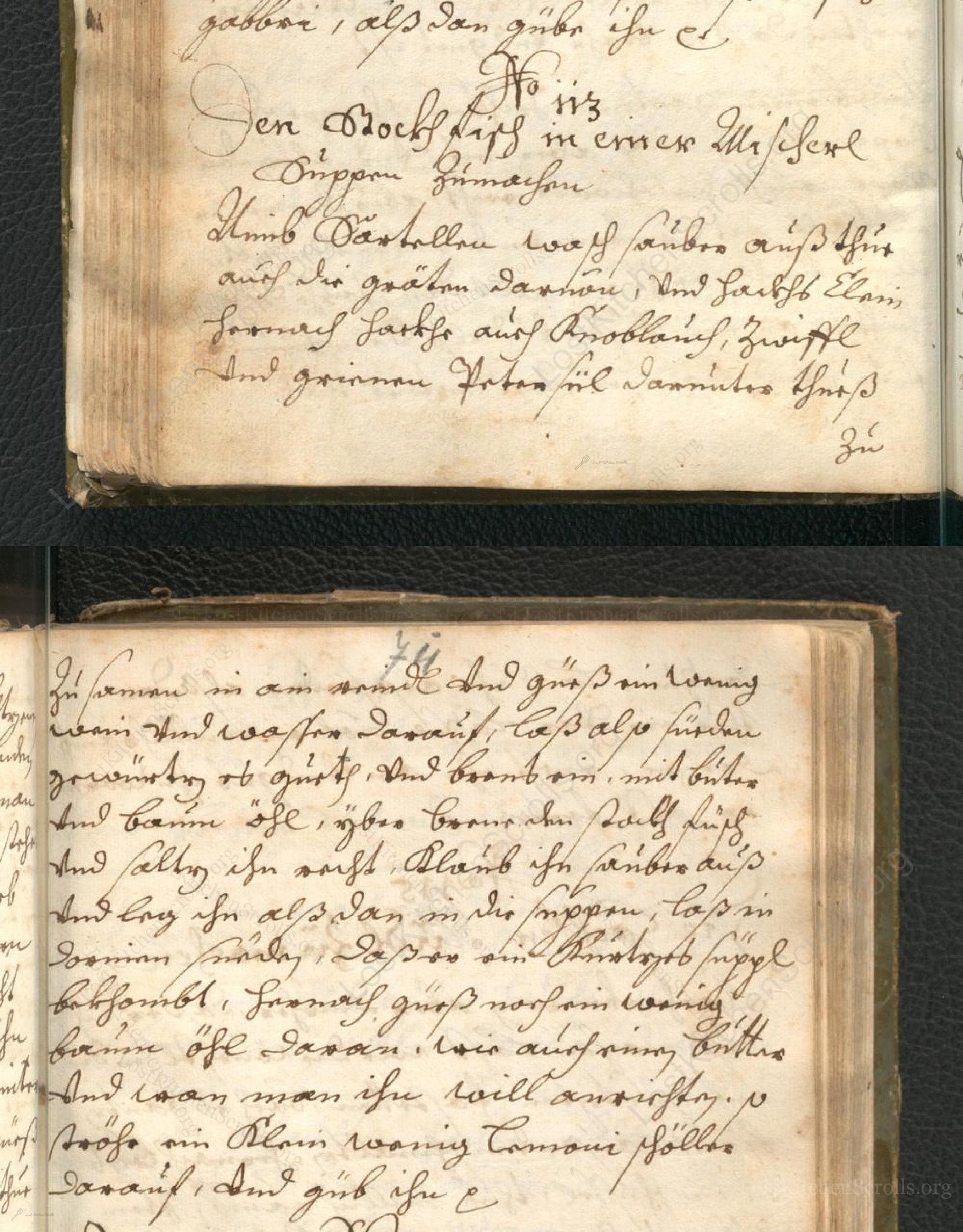

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes