Pour Faire Les Cheueulx Noirs

"To Make Hair Black"

From the treasured pages of Bastiment de receptes

Unknown Author

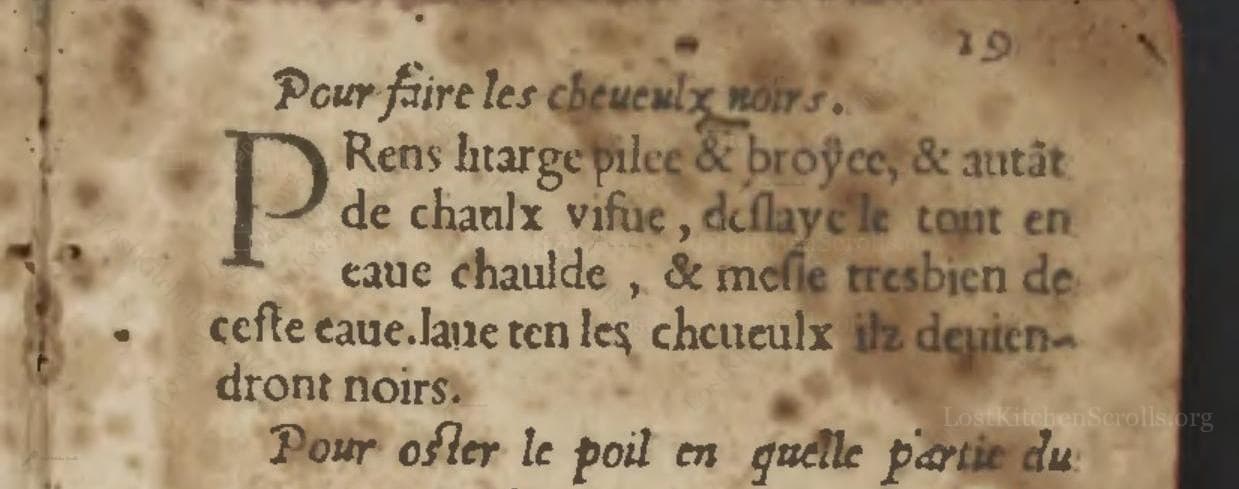

Pour Faire Les Cheueulx Noirs

"Prens litarge pilee & broyee, & autât de chaulx viue, deslaye le tout en eaue chaulde, & mesle tresbien de ceste eaue. laue en les cheueulx ilz deuiendront noirs."

English Translation

"To make hair black. Take pounded and ground litharge and as much quicklime, dissolve all in hot water, and mix this water very well. Wash the hair in it and they will become black."

Note on the Original Text

The recipe is directly imperative and brisk, meant for a literate but busy reader. Punctuation and spelling reflect mid-16th-century French, with many words now obsolete or differently spelled ('cheueulx' for 'cheveux'). Quantities are vague—'autant' meaning 'the same amount'—requiring practical knowledge. Recipes from this era often left crucial safety and measurement details implicit, relying on the experience and judgement of the reader. There was little concept of chemical toxicity, so ingredients like litharge and quicklime were commonly used despite their health risks.

Title

Bastiment de receptes (1541)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Unknown

Era

1541

Publisher

A Lescu de Coloigne

Background

Step into the culinary secrets of Renaissance France! 'Bastiment de receptes' is a delectable compendium newly translated from Italian, brimming with recipes, curious odors, and medicinal tidbits designed to both delight the palate and preserve health.

Kindly made available by

Library of Congress

This recipe comes from 'Bastiment de receptes', printed in Lyon in 1541 by François and Jean Frellon. The volume is a vibrant collection of practical secrets and everyday remedies, translated from Italian into French for a curious Renaissance audience. This particular formula falls into the tradition of cosmetic recipes: clever, experimental, and sometimes hazardous. In 16th-century Europe, darkening hair was a fashionable way to combat grey or pale hair, influenced by ideals from both Italy and France. Recipes frequently mingled the boundaries between practical remedies and alchemical experiment, reflecting both medical theory and beauty standards of the period.

The ingredients would be crushed with a mortar and pestle, a ubiquitous tool found in most Renaissance kitchens and apothecaries. Mixing was probably done in ceramic or wooden bowls, avoiding metal since the reactive ingredients could cause corrosion. Water was gently warmed over a hearth or open flame. Application to the hair would have been by hand or with a linen cloth.

Prep Time

5 mins

Cook Time

0 mins

Servings

1

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- Litharge (lead monoxide), finely crushed (approx. 0.35 oz, historical ingredient, NOT recommended for use)

- Quicklime (calcium oxide), equal amount to the litharge (approx. 0.35 oz, historical ingredient, NOT recommended for use)

- Warm water (3.4-6.8 fl oz)

Instructions

- To make hair black: Take powdered litharge (lead monoxide) and an equal amount of quicklime (calcium oxide).

- Mix both thoroughly, and dissolve them in warm water.

- Use this water to wash your hair.

- The hair will become black.

- IMPORTANT: Please note, litharge and quicklime are dangerously toxic substances and are not safe or legal for cosmetic use today.

- For a modern, safe version, do not attempt to replicate this recipe.

Cooking Estimates

This historical recipe takes only a few minutes to mix the powders and dissolve them in water. There is no cooking or waiting time. Since this is a topical hair wash, not food, there are no calories. The yield is for one hair wash.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

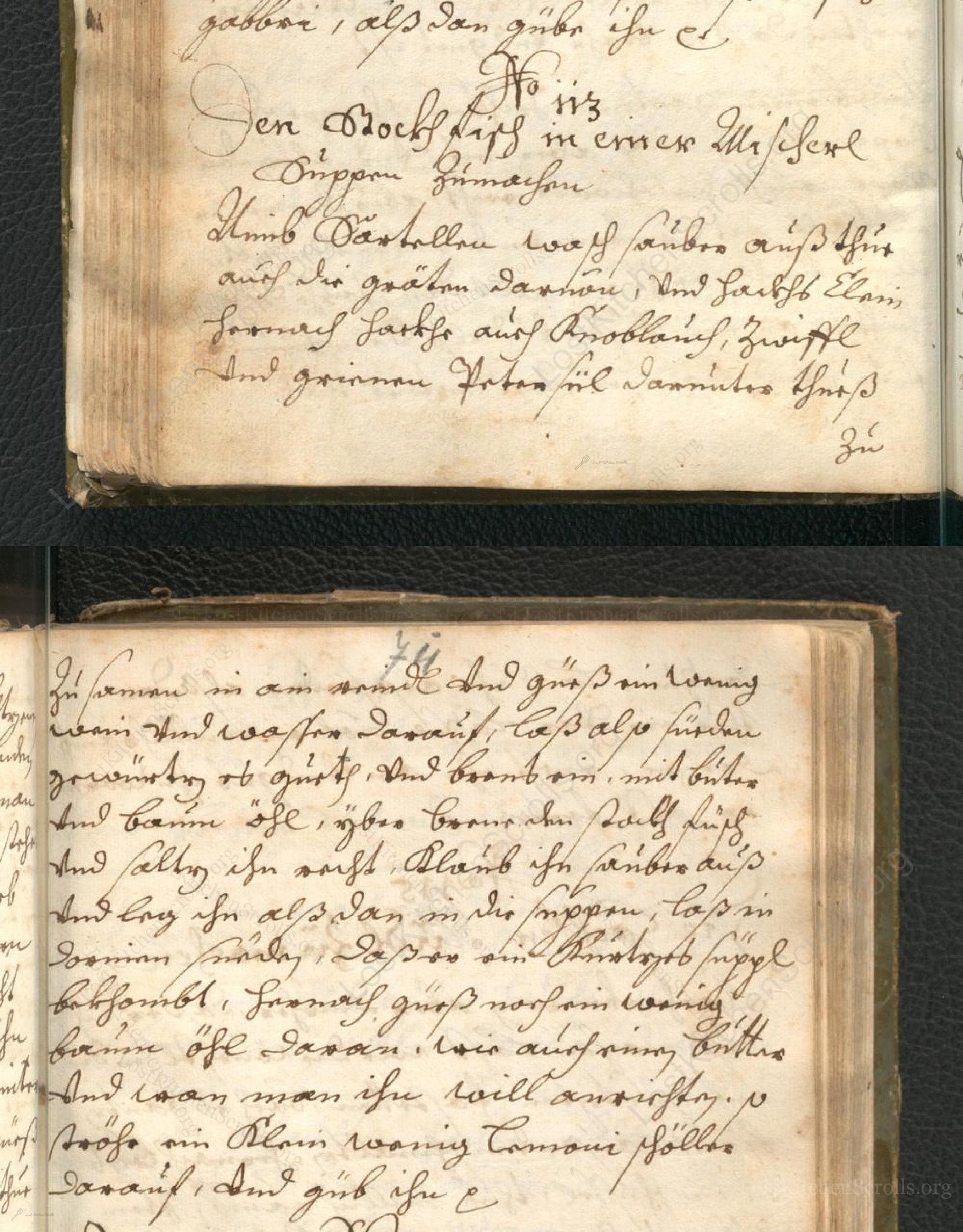

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes