To Make Snaile Water

From the treasured pages of Receipts in cookery and medicine 1700

Unknown Author

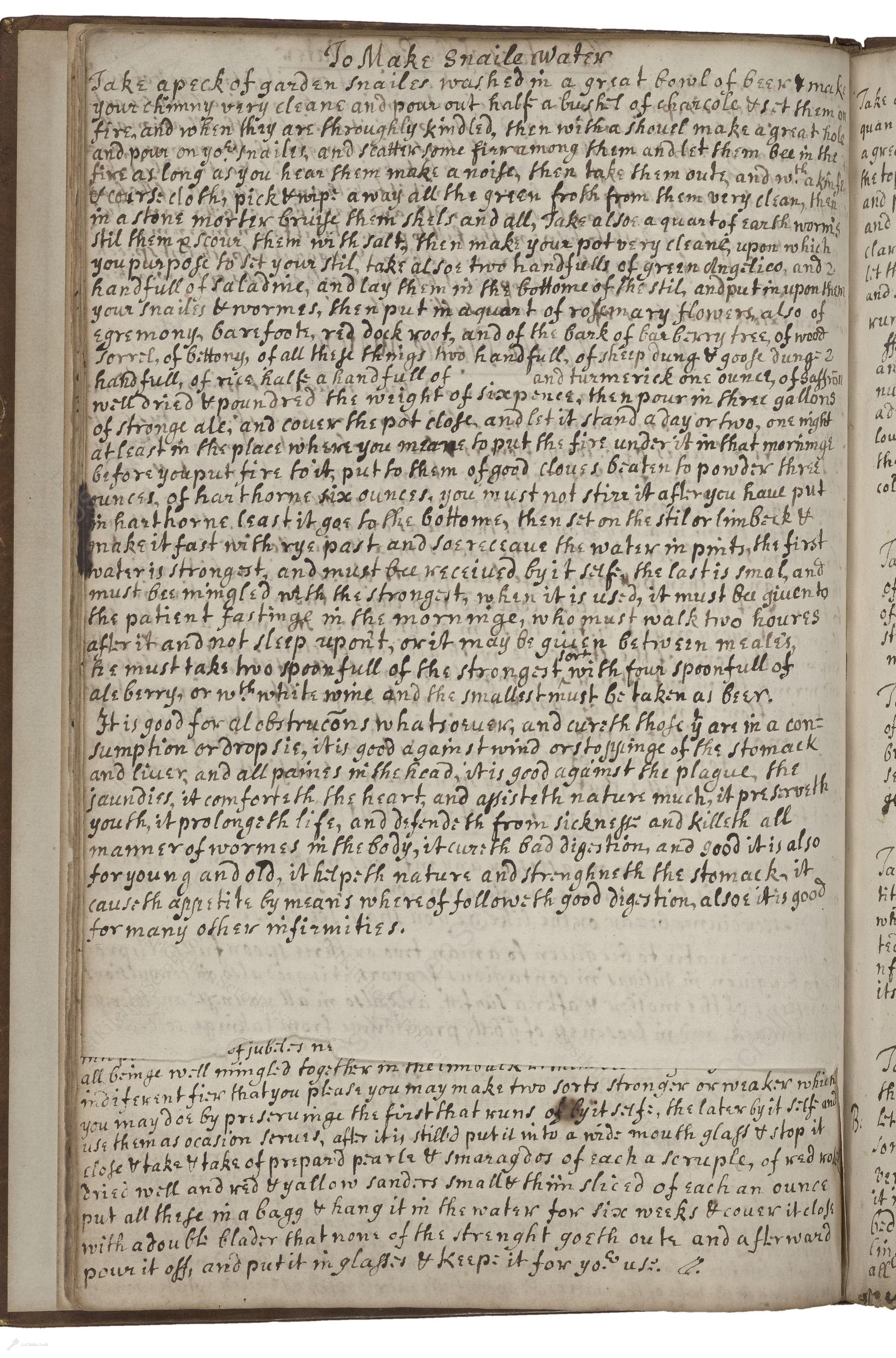

To Make Snaile Water

"Take a peck of garden snails, and wash them in a great bowl of beer & make your chimney very cleane and pour out half a bushell of charcole & set them on fire, and when they are throughly kindled, then with a shovel make a great hole in the middest of some fire among them and let them bee in the fire as long as you hear them make a noise, then take them out, and with a knife & course cloth, pick & wipe away all the green froth from them very clean, then in a stone morter bruise them shells and all, take alsoe a quart of earth worms, scil them & scour them with salt, then make your pot very cleane, upon which you purpose to set your stil, take two handfulls of green angelico, and 2 handfuls of Saladine, and lay them in the bottome of the stil, and put in upon them your snailes & wormes, then put in a quart of rosemary flowers, alsoe of egremony, barefoot, red dock, sorril, of bettony, of all these things two handfuls of each also two handfulls of sheep dung & goose dung, 2 handfuls of rice half a handfull, of wood soot, and of the bark of barberry tree, of woodbine well dried & poundred the weight of sixpence, and turmerick one ounce, of saffron the weight of sixpence, then pour in three gallons of stronge ale, and cover the pot close and let it stand a day or two, one night at least in the place where you mean to put the fire under it in that morning before you put fire to it, put to it one ounce of cloves beaten to powder three ounces, of harthorne six ounces, you must not stire it after you have put in harthorne least it goe to the bottome, then set on the stil or limbeck & make it fast with rye past, and soe receave the water in pints, the first water is strongest, and must be receaved by itself, the last is smal, and must be mingled with the strongest, when it is used, it must be given to the patient fasting in the morninge, who must walk two houres after it and not sleep upon it, or it may be given between meales, the strongest with four spoonfuls of ale berry, or with white wine and the smallest must be taken as beer. It is good for all obstructions which causeth a consuption or dropsie, it is good against wind or stoppinge of the stomack and liver, and all paines in the head, it is good against the plague, the jaundiss, it comforteth the heart, and assisteth nature much, it preserveth youth, it prolongeth life, and defendeth from sicknesse and killeth all manner of wormes in the body, it cureth bad digestion, and good it is also for youg and old, it helpeth nature and stringthneth the stomack, it causeth an apetite by means of sweat, if it be followed with good digestion, alsoe it is good for many other infirmities. you may make two sorts stronger or weaker which of that runs of by itself, the later by itself and stilld put it into a wide mouth glass & stop it close & take of prepared pearls driede well and red & yallow sanders of each a scruple, of red rose leaves small & thin sliced of each an ounce, put all these in a bagg & hang it in the water for six weeks & cover it close with a double blader that none of the strenght goeth out, and afterward pour it off and put it in glass & keep it for yo:r use. &c."

Note on the Original Text

As was common in early modern English manuscripts, the recipe is written as a continuous block of prose with minimal punctuation, largely omitting standardized spelling and measurements. Directions are embedded in narrative form—no ingredient lists or step-by-step breakdowns! Measures rely on traditional household units like 'peck,' 'handful,' and the 'weight of a sixpence,' which can be approximated but are not exact. Spelling variations—'bettony' for betony, 'egremony' for agrimony, and so on—are typical for the time, as spelling was not standardized. The text also assumes a high level of familiarity with kitchen process and implied knowledge—distilling was a skilled, and sometimes secretive, craft. This recipe exemplifies a hands-on, experience-led approach to kitchen medicine, expecting the reader to fill in gaps from their household's own traditions.

Title

Receipts in cookery and medicine 1700 (1700)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Unknown

Era

1700

Publisher

Unknown

Background

Step into the kitchen of the early 18th century, where this charming culinary manuscript tempts tastebuds with recipes and secrets from a bygone era. A delicious journey for both the curious cook and the history lover.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

This recipe, titled "To Make Snaile Water," appears in an English household manuscript around 1700. At the time, remedies distilled from a complex medley of animal, herbal, and mineral ingredients were prized for their supposedly wide-ranging medicinal effects. Snaile Water was thought to address issues from digestive complaints to 'obstructions' to even the plague itself! This concoction reflects the era's humoral practices—the belief that balance could be restored by combining ingredients of varying properties and even animal and mineral origins. Such preparations were a staple in wealthy households with the means to access exotic or labor-intensive components and the equipment to undertake distillation. Snails, worms, and dung, though unpalatable today, were commonly attributed with cooling or cleansing properties, while a riot of botanicals supplied further 'virtues.' The practice of distilling these compounded mixtures for health was prevalent before modern pharmacology rendered such broths obsolete.

The historical kitchen for Snaile Water required a robust hearth or open fire to ignite large quantities of charcoal and facilitate the first stages of animal preparation. Iron or heavy stone mortars and pestles were essential for crushing shells and plant matter. For distillation itself, an alembic or still (often made of copper or pewter) was used, sealed with rye flour paste to prevent vapor loss. Filters or cloths were employed for washing and final clarification, and collection of the distillate was done in ceramic or glass receivers, followed by further infusion in large glass vessels with organic seals like bladder skin. Today, a well-ventilated kitchen, stainless steel or glass bowl, modern mortar and pestle, and preferably a laboratory-grade distillation kit (or at-home distiller) are the safest substitutes.

Prep Time

2 hrs

Cook Time

4 hrs

Servings

40

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 2.4 gal (approx. 15.5 lbs) garden snails

- Beer (for washing, approx. 2 quarts)

- 8.5 gal charcoal

- 1 qt (approx. 2.2 lbs) earthworms (or omit)

- 2 oz fresh angelica leaves

- 2 oz fresh celandine (greater celandine)

- 1 qt rosemary flowers (or 1 oz dried)

- 2 oz agrimony

- 2 oz betony

- 2 oz sorrel

- 2 oz red dock (Rumex spp.)

- 2 oz fresh sheep dung (or omit)

- 2 oz fresh goose dung (or omit)

- 2 oz uncooked rice

- 1 oz wood soot (optional/for authenticity)

- 0.2 oz dried barberry bark

- 0.07-0.1 oz dried honeysuckle stems, powdered

- 1 oz turmeric

- 0.07-0.1 oz saffron

- 3-3.2 gal strong ale (stout/porter preferred)

- 1 oz ground cloves

- 3 oz hawthorn wood (powdered)

- 0.04 oz dried pearls (optional)

- 0.04 oz red sandalwood (santalum powder)

- 0.04 oz yellow sandalwood (if available)

- 1 oz dried red rose petals

Instructions

- To craft a 21st-century version of Snaile Water, begin by thoroughly washing roughly 2.4 gallons (approx.

- 15.5 lbs) of fresh garden snails in a large bowl of beer.

- Prepare a charcoal fire, letting about 8.5 gallons (half a bushel) of charcoal ignite until fully heated.

- Place the snails in the hot charcoal until no further sizzling is heard, indicating moisture has cooked off.

- Retrieve, then scrub away any froth with a coarse cloth and knife.

- Pound snails and shells in a sturdy mortar.

- Scald and salt approximately 1 quart (about 2.2 lbs) of earthworms, rinse well.

- Layer 2 oz (two handfuls) each of fresh angelica leaves and celandine, followed by the snail and worm mixture, into a clean large pot.

- Add 1 quart of rosemary flowers, plus 2 oz (two handfuls) each of agrimony, betony, sorrel, red dock, and 2 oz each of fresh sheep and goose manure (if not available, omit or substitute composted plant fertilizer).

- Add 2 oz uncooked rice, 1 oz wood soot (approximate; or omit for safety), bark of barberry, and dried powdered honeysuckle stems (weight of a small coin, about 0.07-0.1 oz).

- Mix in 1 oz turmeric, and a small pinch (about 0.07-0.1 oz) of saffron.

- Pour over 3 to 3.2 gallons of strong ale (modern stout).

- Let the mixture steep for at least 24 hours.

- Before distillation, grind 1 oz cloves, and add 3 oz powdered hawthorn wood, letting it settle without stirring.

- Distil using a traditional or modern still, forming a tight seal with dough.

- Collect the condensed liquid (distillate) in batches—the first (about 1 pint) being strongest.

- Store in well-sealed bottles.

- For finishing, suspend a sachet with 0.04 oz dried pearls, 0.04 oz each red and yellow sandalwood, and 1 oz thinly sliced dried rose petals in the liquid for six weeks before decanting for medicinal use.

Estimated Calories

50 per serving

Cooking Estimates

Preparing Snaile Water takes time: you need to wash and cook snails, clean worms, layer herbs and other ingredients, let it soak, and then distill it. Most of the time is hands-off except for distilling, which can take a few hours. This recipe produces about 10 liters of finished liquid, and we estimate about 40 servings at 250 ml each. Calories per serving are very low, as the distillation removes most solids and the alcohol is modest.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes