To Make Cowslip Wine

From the treasured pages of Receipt book

Unknown Author

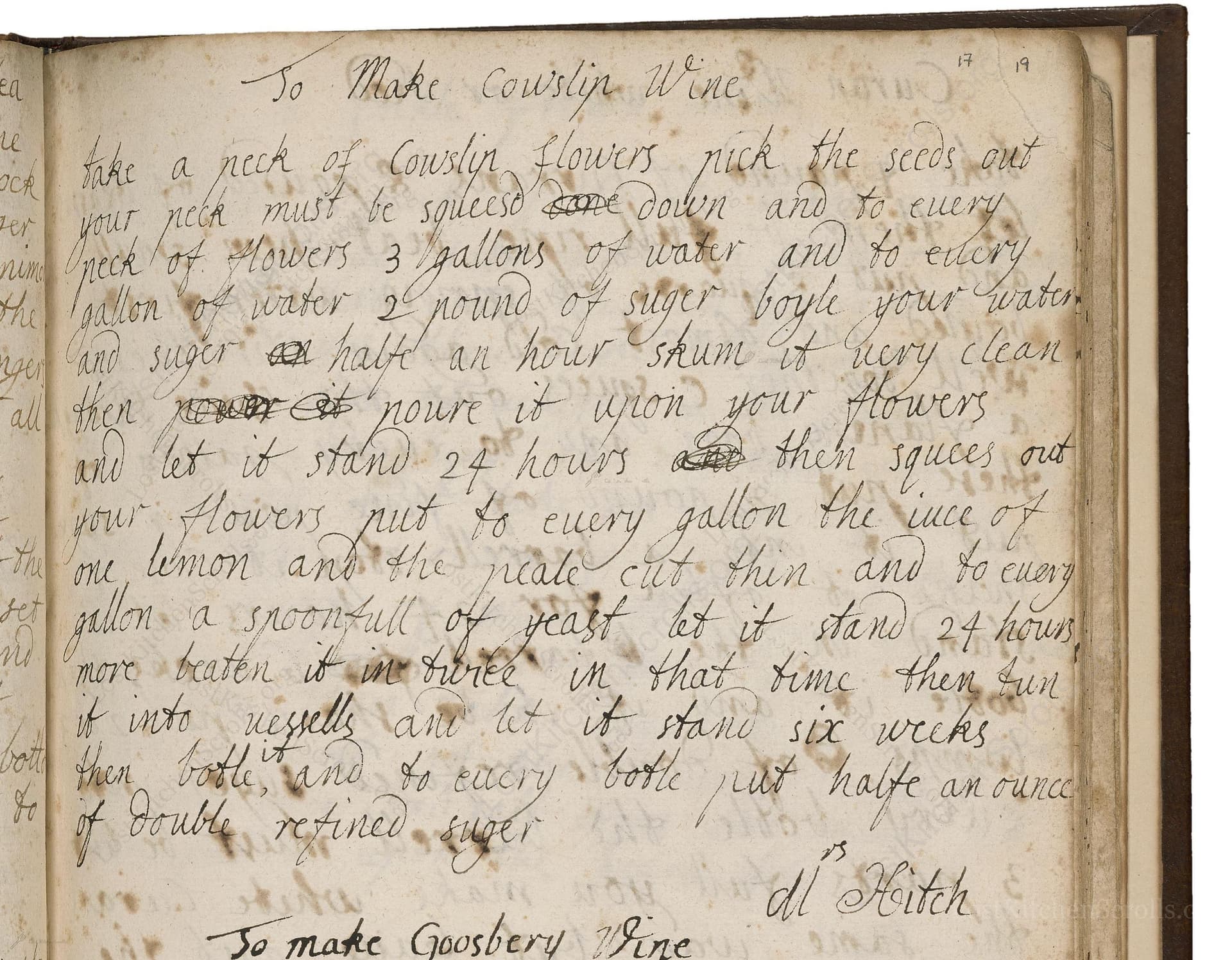

To Make Cowslip Wine

"take a peck of Cowslip flowers pick the seeds out your peck must be squeesed down and to every peck of flowers 3 gallons of water and to every gallon of water 2 pound of suger boyle your water and suger an halfe an hour skum it very clean then poure it upon your flowers and let it stand 24 hours then squees out your flowers put to every gallon the iuce of one lemon and the peale cut thin and to every gallon a spoonfull of yeast let it stand 24 hours more beaten it in twice in that time then tun it into vessells and let it stand six weeks then botle, and to every botle put halfe an ounce of double refined suger Ms Hitch"

Note on the Original Text

The recipe is written in the vernacular of the time, making spelling less consistent ('boyle' for boil, 'suger' for sugar, 'skum' for skim, 'squees' for squeeze, 'vessells' for vessels, 'botle' for bottle). Measurement units such as 'peck' and 'gallon' refer to pre-metric English sizes (peck = ~9 liters uncompressed, gallon = 4.54 liters imperial). Instructions are terse and assume a familiarity with basic household brewing techniques. Specifics like fermentation temperatures or times are left to the judgment and experience of the cook, reflecting the hands-on, sensory-based approach to early modern English cookery.

Title

Receipt book (1700)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Unknown

Era

1700

Publisher

Unknown

Background

A delightful glimpse into the kitchens of the early 18th century, this historic culinary manuscript promises a feast of recipes, remedies, and perhaps a pinch of mystery. Expect both practical fare and elegant inspiration for the curious cook.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

This recipe comes from an English manuscript, V.b.272, dating to around 1700. Cowslip wine was a favorite among households with access to rich meadows, where cowslip flowers were abundant in spring. Making flower wines was a way to capture the fleeting taste and aroma of spring, celebrating both the skills and social rituals of early modern homes. Such wines were homemade luxuries, often produced by women in the household, and served at family gatherings or to honored guests. The recipe reflects an era when sugar was becoming more accessible in England, and when the natural yeasts from air or brewing was the norm rather than commercial yeast.

In the early 18th century, cooks would have used large earthenware or wooden tubs for steeping the flowers and boiling cauldrons or large pots over open fires for making the sugar syrup. Straining was done with cloths or fine sieves. Wooden spoons and ladles would be used for stirring, and fermentation occurred in wooden casks or stoneware jugs. Bottling required hand-blown glass bottles, corks, and wax to seal. Precision measuring tools were uncommon; quantities were measured by sight, by the peck (a standard market measure for dry goods), by jugs, or by handfuls.

Prep Time

9 hrs

Cook Time

30 mins

Servings

20

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 2 pecks packed cowslip flowers (or, if unavailable, dried cowslip petals from reputable suppliers, or substitute primrose flowers)

- 3 imperial gallons water

- 15 pounds white granulated sugar

- 3 lemons (juice and thinly peeled zest)

- 3 tablespoons (1.5 fl oz) active dry yeast

- 3 oz caster sugar for bottling (0.5 oz per 26 fl oz/750 ml bottle)

Instructions

- To make Cowslip Wine with imperial measures, start with about 2 pecks of tightly packed cowslip flowers (a historical 'peck' was roughly 2 gallons; when packed, this would be about 2 pecks, or 4 gallons, by volume).

- Remove all stems and seeds from the flowers.

- For every 2 pecks (4 gallons) of flowers, bring 3 imperial gallons of water (13.5 quarts or 6.8 pints per gallon, total 39 imperial pints) to the boil with 15 pounds of white granulated sugar (2 pounds per imperial gallon, total of 6 pounds per 1 imperial gallon, or 15 pounds for 3 gallons).

- Boil this for 30 minutes, skimming off any foam, then pour the syrup over the cowslip flowers and let the mixture steep for 24 hours.

- The next day, strain and squeeze the flowers well to extract as much flavor as possible.

- To the resulting liquid, for every 1 imperial gallon (4.55 liters), add the freshly squeezed juice of one lemon and the thinly peeled rind of that lemon.

- Add 1 tablespoon (about 0.5 fl oz) of active dry yeast per imperial gallon.

- Let this ferment for another 24 hours, stirring at least twice.

- Transfer the liquid to fermentation vessels, leave to ferment in a cool place for six weeks, then bottle.

- For each 26 fl oz (750 ml) bottle, add about 0.5 oz (14 grams) of caster sugar to sweeten before sealing.

- Let the wine mature in bottle for a few months before drinking.

Estimated Calories

190 per serving

Cooking Estimates

Gather the cowslip flowers and prepare the ingredients. Boil water with sugar, then let the syrup steep with the flowers for 24 hours. The next day, add lemon and yeast, ferment for another 24 hours, then transfer to ferment for 6 weeks before bottling. Each serving of wine has about 190 calories. This recipe makes about 20 bottles (750 ml each) of wine.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Dietary Preference

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes