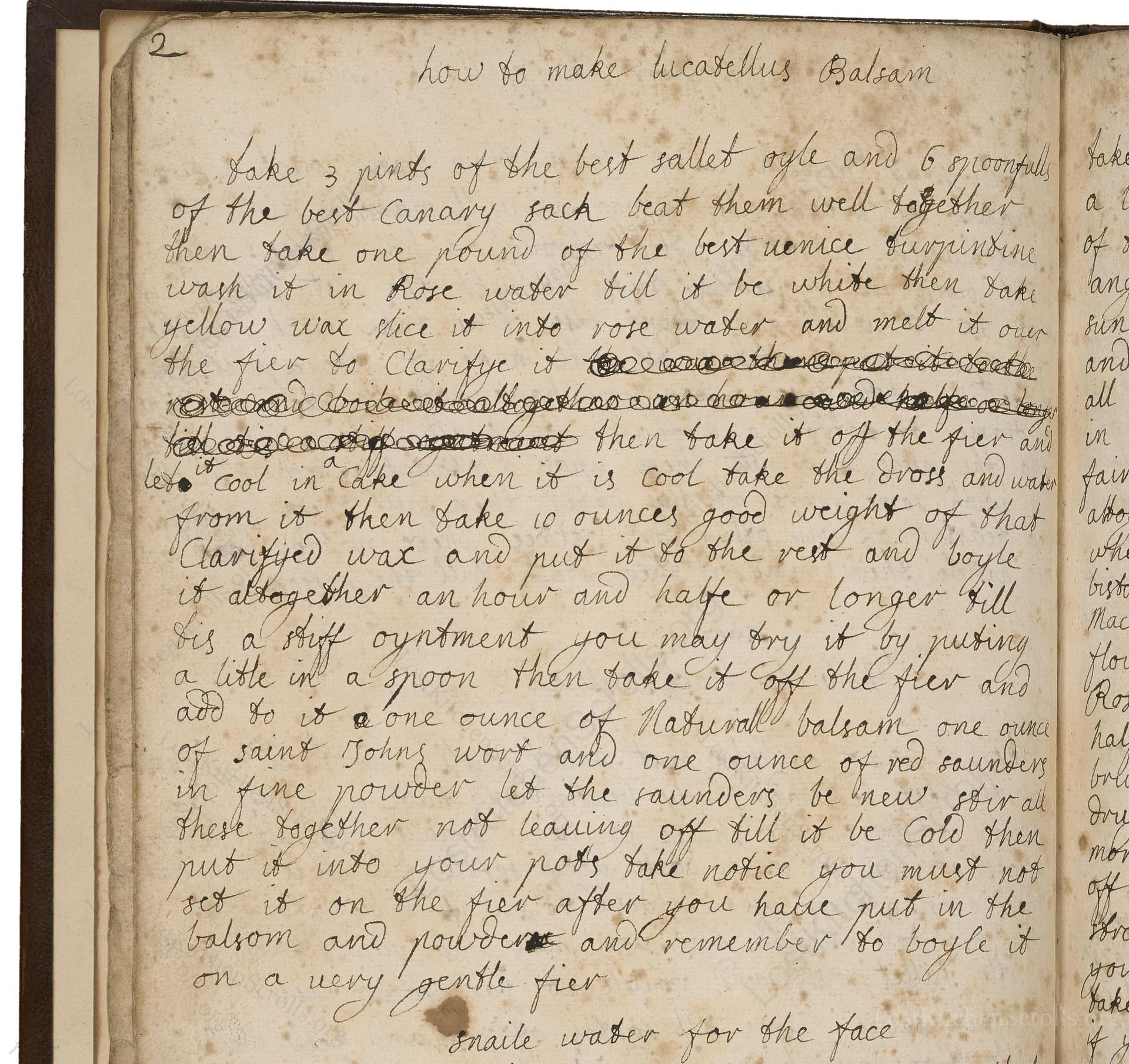

How To Make Lucatellus Balsam

From the treasured pages of Receipt book

Unknown Author

How To Make Lucatellus Balsam

"Take 3 pints of the best sallet oyle and 6 spoonfulls of the best canary sack beat them well together then take one pound of the best venice turpentine wash it in Rose water till it be white then take yellow wax slice it in rose water and melt it our the fier to Clarifye it then take it of the fier and lett it cool in a cake when it is cool take the dross and water from it. then take 10 ounces good weight of that Clarifyed wax and put it to the rest and boyle it altogether an hoür and halfe or longer till tis a stiff oyntment you may try it by putting a litle in a spoon then take it off the fier and add to it a one ounce of Naturall balsam, one ounce of saint Johns wort and one ounce of red saunders in fine powder let the saunders be new stir all these together not leaving off till it be Cold then put it into your pots take notice you must not set it on the fier after you have put in the balsom, and powder and remember to boyle it on a very gentle fier."

Note on the Original Text

Early eighteenth-century recipes such as this one are often written in a continuous stream of instructions—minimal punctuation, variable spelling ('boyle', 'clarifye', 'oyntment'), and little distinction between weights/volumes. The language presumes a working knowledge of kitchen tasks and ingredient handling, typical for literate housewives or household stewards. Abbreviations and period-specific names—like 'sallet oyle' for salad or olive oil and 'canary sack' for a sweet fortified wine—testify to evolving food terminology. Clarity comes from context, and directions lean on practice over precise timings or temperatures common to modern procedure.

Title

Receipt book (1700)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Unknown

Era

1700

Publisher

Unknown

Background

A delightful glimpse into the kitchens of the early 18th century, this historic culinary manuscript promises a feast of recipes, remedies, and perhaps a pinch of mystery. Expect both practical fare and elegant inspiration for the curious cook.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

Lucatellus Balsam hails from early modern Europe—in this case, England circa 1700, as found in manuscript V.b.272. Balsams like this were prized household remedies for wounds and skin ailments, blending exotic resins and familiar local ingredients. Its Venetian and Mediterranean influences recall the cross-cultural exchanges of the era, when apothecaries merged classical and folk medicine to produce versatile ointments. Such recipes circulated widely among literate households, often copied into family compendia. Their presence in English manuscripts offers a fascinating window onto domestic medicine before the professionalization of pharmacy and the rise of standardized remedies.

The original maker would have used glazed earthenware or metal pots for mixing and heating, wooden spoons or spatulas for stirring, and a gentle open hearth fire (possibly with a trivet or sand bath for even, low heat). Cheesecloth or muslin may have helped strain impurities; rose water and other ingredients were stored in glass or ceramic bottles. For washing and clarifying, shallow bowls were employed. The finished balsam was poured into small ceramic jars or pots—sometimes with waxed paper or vellum covers.

Prep Time

1 hr

Cook Time

1 hr 30 mins

Servings

20

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 1.5 quarts (6 cups) olive oil (sallet oyle)

- 3 fl oz (6 tbsp) dry sherry or Madeira (substitute for canary sack)

- 1 lb Venice turpentine (or larch/pine turpentine)

- enough rose water to wash and rinse

- 10 oz yellow beeswax

- 1 oz balsam of Peru or storax (as a substitute for 'naturall balsam')

- 1 oz dried, ground St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

- 1 oz powdered red sandalwood (Pterocarpus santalinus)

Instructions

- To make Lucatellus Balsam with contemporary equivalents, begin by measuring 1.5 quarts (6 cups) of the highest quality olive oil (sallet oil) and about 3 fluid ounces (6 tablespoons) of a dry fortified white wine such as sherry (as a stand-in for canary sack).

- Mix these well.

- Next, take 1 pound (1 lb) of pure Venice turpentine (pine resin, or substitute organic larch or pine turpentine), and repeatedly wash it in rose water until it takes on a whitish hue.

- Slice 10 ounces of yellow beeswax (warmed and sliced thinly for easier melting) and rinse it briefly in rose water.

- Melt the wax gently, skimming off impurities, and let it cool—removing any settled dross and water.

- Once clarified, weigh out 10 ounces and add this to your oil, wine, and turpentine, then heat the mixture gently for 90 minutes or until it thickens to a stiff salve (test by dropping some onto a spoon to check for texture).

- Remove from heat and stir in 1 ounce each of balsam of Peru or storax (as natural balsam), dried and ground St.

- John's Wort, and red sandalwood powder, ensuring the sandalwood is freshly ground.

- Continue stirring until the mixture cools and thickens, then transfer to sterilized jars.

- Do not reheat after adding the powders and balsam, and always maintain a low, gentle heat throughout.

Estimated Calories

275 per serving

Cooking Estimates

Preparing Lucatellus Balsam takes time because you need to rinse and clarify ingredients like turpentine and beeswax before mixing and gently heating them together. After adding the powders and balsam, you stir until cool. The cooking and prep times below include all key steps.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Dietary Preference

Main Ingredients

Occasions

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes