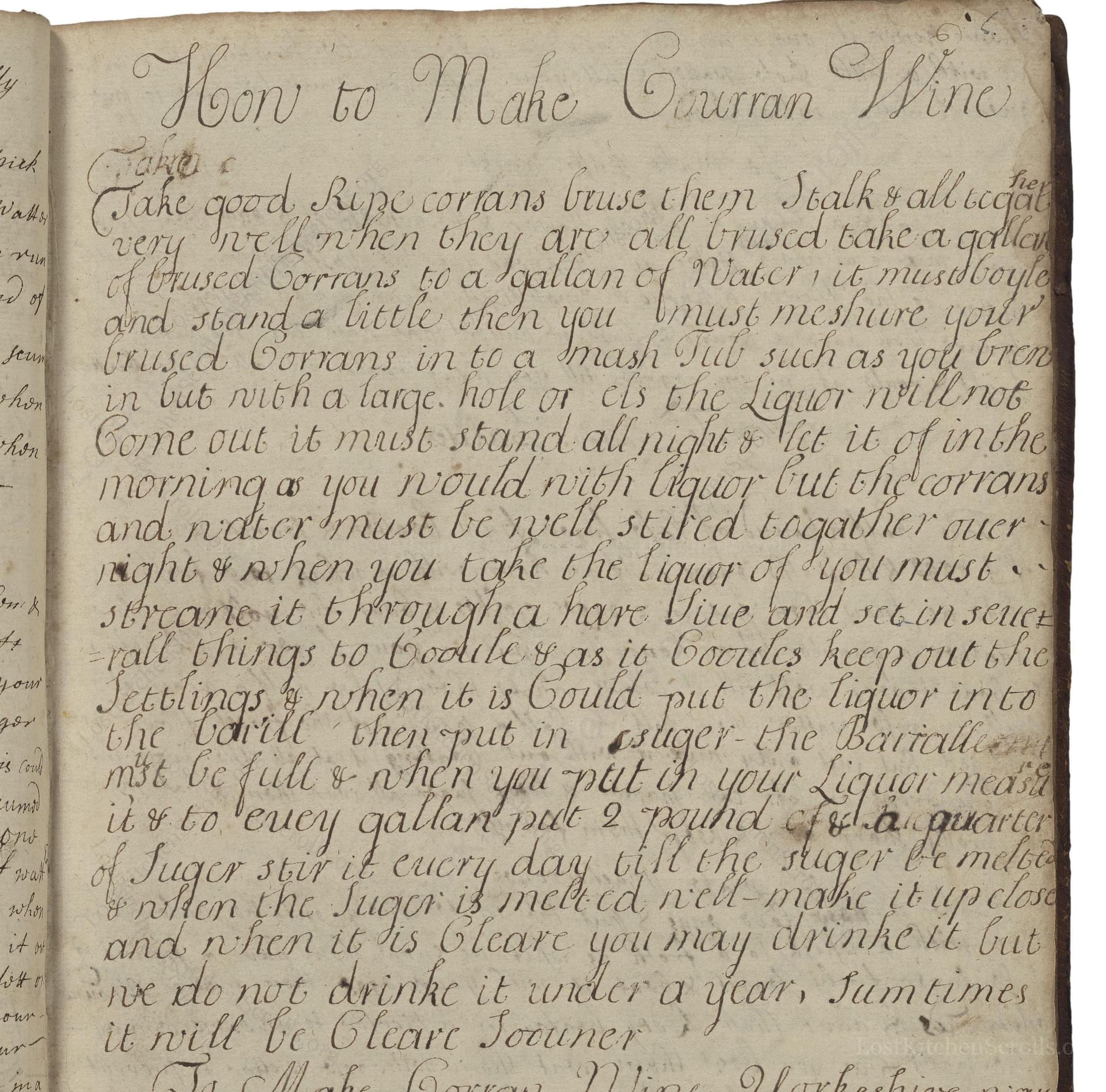

How To Make Courran Wine

From the treasured pages of Mrs. Rachel Kirk Book 1707

Written by Rachel Kirk

How To Make Courran Wine

"Take good Ripe corrans bruse them Stalk & all togather very well when they are all brused take a gallon of brused Corrans to a gallan of Water it must boyle and stand a little then you must meshure your brused Corrans in to a mash tub such as you brew in but with a large hole or els the liquor will not come out it must stand all night & let it of in the morning & you would put the liquor but the corrans and water must be well stired togather over night & when you take the liquor of you must streane it through a hare sive and set in severall things to coole & as it cooles keep out the Settlings & when it is could put the liquor into the barill then put in suger the Barill must be full & when you put in your liquor measur it & to every gallan put 2 pound & a quarter of Juger stir it every day till the suger be melted & when the Juger is melted well make it up close and when it is cleare you may drinke it but we do not drinke it under a year. Sumtimes it will be cleare Sooner"

Note on the Original Text

The recipe is written in 18th-century English, featuring non-standardized spelling (e.g., 'corrans' for currants, 'boyle' for boil, 'Jugger' for sugar) and imprecise measurements, as was typical for the era. Instructions were often given for those familiar with the processes, expecting readers to understand implicit steps. Poor punctuation and run-on sentences are common, emphasizing oral tradition and practical experience over literary precision. Recipes from this period prioritize process (steeping, straining, fermenting) over measurement or timing, trusting the cook to judge readiness by look and feel. Details like leaving the wine to clear for a year shows the importance of patience and observation in early modern kitchens.

Title

Mrs. Rachel Kirk Book 1707 (1707)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Rachel Kirk

Era

1707

Publisher

Unknown

Background

A remarkable collection of early 18th-century recipes, Rachel Kirk's work invites readers into the kitchens of the past where classic culinary traditions and timeless flavors come alive. Expect a charming medley of savory feasts and sweet treats reflective of the era's sophisticated palate.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

This recipe originates from Rachel Kirk in 1707, a period when country housewives throughout Britain crafted fruit wines as an alternative to expensive imported grape wines. Currants (or "corrans") were common in kitchen gardens, and such wines were popular for household consumption and preserving the harvest. Homemade wines were a symbol of resourcefulness and social standing, reflecting domestic culinary skills passed from one generation to the next. At the time, there was little standardization in recipes, so exact measurements depended on local practices and the cook's experience. This method, calling for a yearlong wait, reflects the patience and anticipation characteristic of historical home brewing and celebrates the slow pleasures of the season.

The original process would have used a large mash tub, similar to those used in brewing, with a spigot or a large hole for draining the liquid, a wooden or stone pestle for crushing the currants, a 'hair sieve' (coarse cloth or fine-mesh strainer made from animal hair) for straining, and wooden barrels for fermenting and aging. Simple wooden stirring paddles and earthenware or stoneware jugs for storage would be typical. Cooling was done by transferring the liquid to various shallow vessels before fermentation. Today, equivalent tools include a large fermentation bucket, potato masher, fine-mesh strainer or cheesecloth, demijohn or carboy for fermentation, airlocks, and food-grade plastic or glass bottles for aging.

Prep Time

35 mins

Cook Time

10 mins

Servings

7

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 2.2 lbs ripe currants (red, black, or white), fresh or frozen if fresh unavailable

- 1 quart water

- 9.7 oz granulated sugar per every quart juice

- Optional: wine yeast (if relying on wild yeast is not desired)

Instructions

- Start by taking ripe currants (either red, black, or white), removing any large stems but leaving small ones, and crushing the fruit thoroughly.

- For every quart of crushed currants, add 1 quart of water.

- Bring the water to a boil, pour over the currants, and let the mixture cool slightly.

- Transfer everything to a large fermentation tub, cover, and leave to steep overnight.

- The following morning, strain the mixture well through a fine sieve to extract the juice, discarding the solids.

- Allow the liquid to cool completely, and as it settles, decant off the clear juice, leaving behind any sediment.

- Measure the liquid and for each quart, stir in 9.7 ounces of sugar until dissolved.

- Pour into a clean fermentation vessel (such as a demijohn or barrel), ensuring it is full, and seal it loosely to allow fermentation gases to escape.

- Stir daily until the sugar is fully dissolved.

- When fermentation subsides and the wine runs clear (which may take several months), bottle and age for at least a year before drinking for best results.

Estimated Calories

140 per serving

Cooking Estimates

It takes about 10 minutes to clean and crush the currants, and about 10 minutes to boil and pour the water. The mixture soaks overnight, and then you strain and prepare the juice the next morning for about 15 minutes. The cooking part is only the boiling water. Each glass of this homemade currant wine has about 140 calories, and this recipe makes about 7 servings (as standard wine glasses from 1 litre wine bottle equivalent).

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Dietary Preference

Main Ingredients

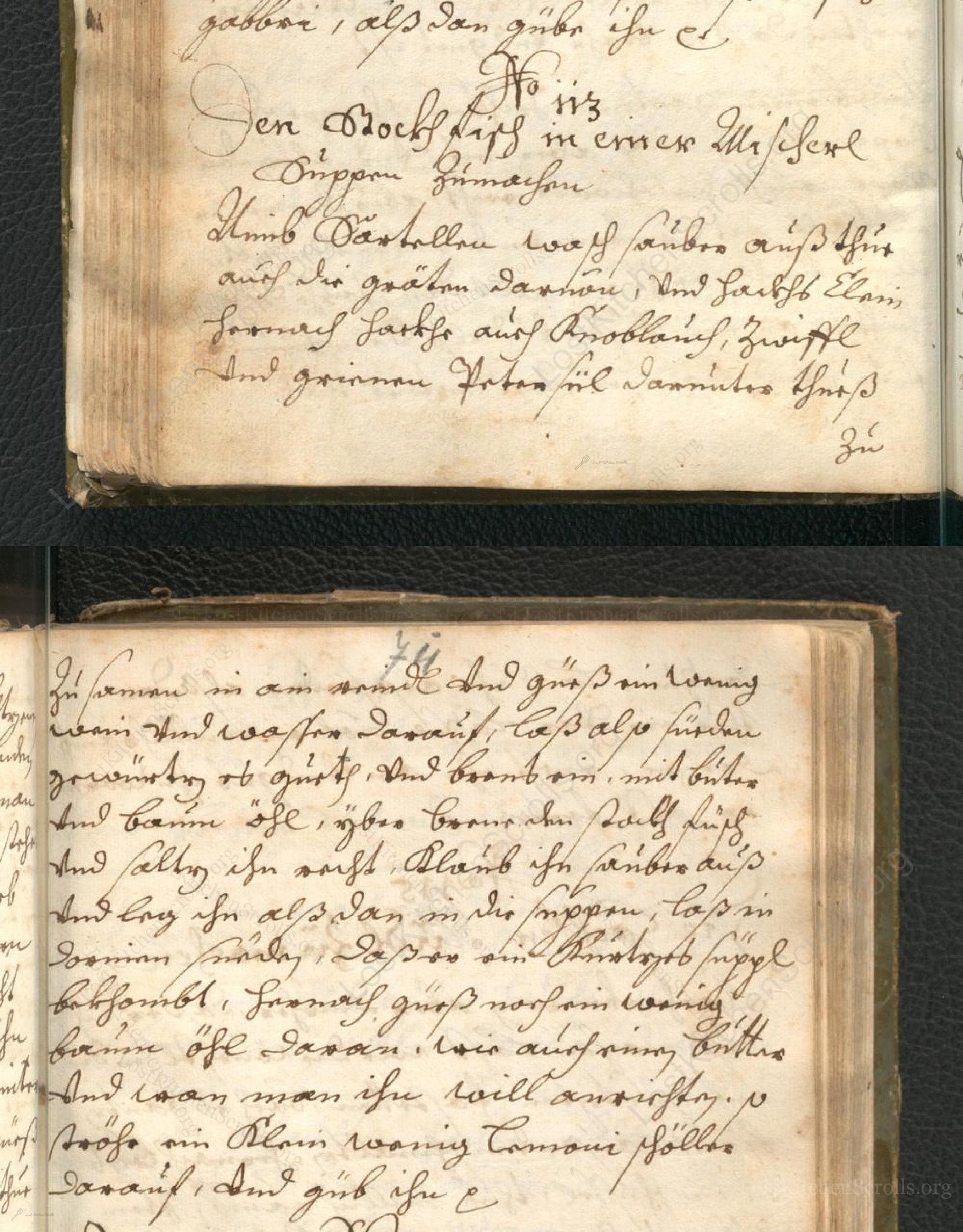

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes