To Make Cowslip Wine

From the treasured pages of Cookery book of Ann Goodenough

Written by Ann Goodenough

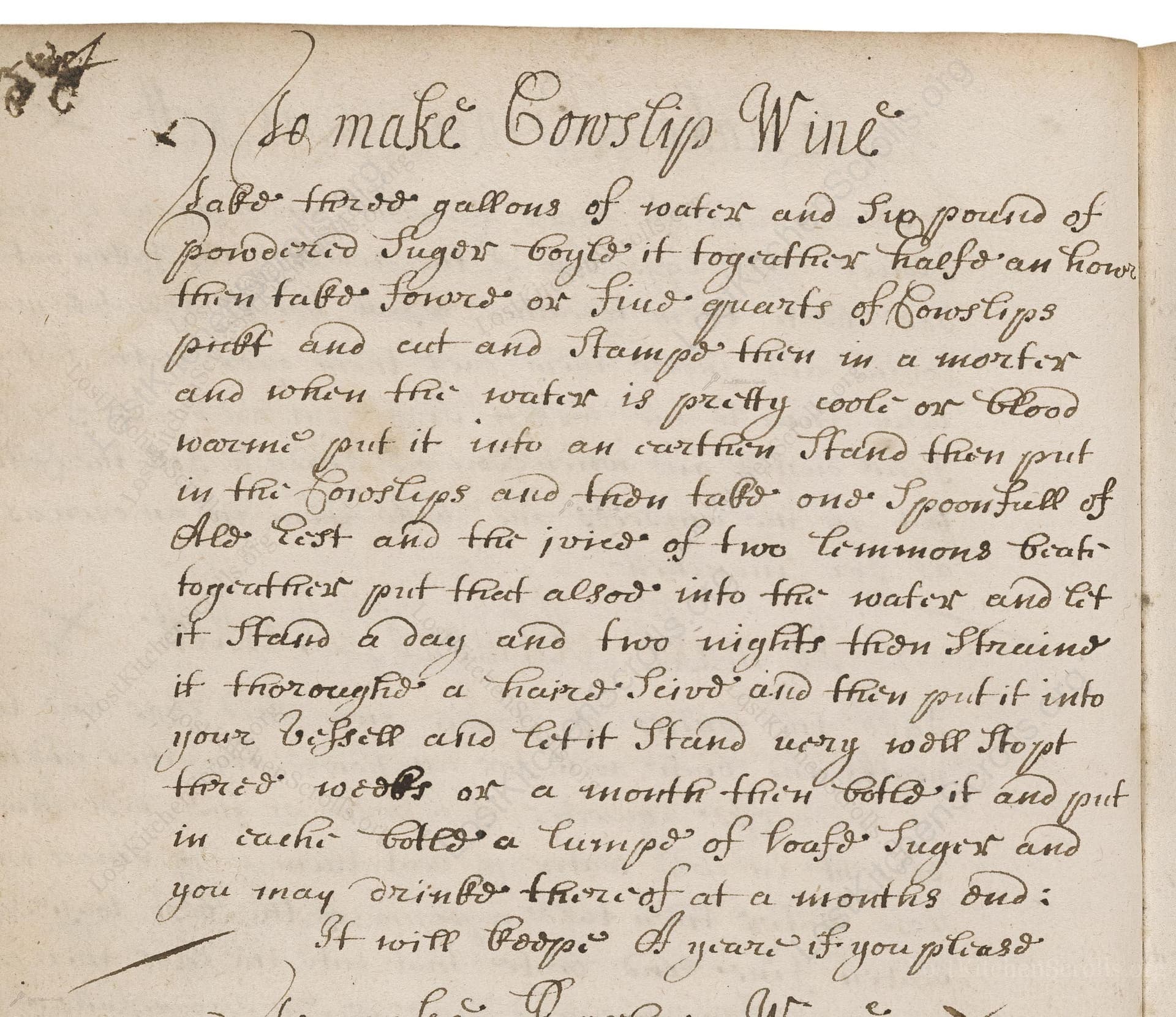

To Make Cowslip Wine

"Take three gallons of water and six pound of powdered Sugar boyle it togither half an hour thin take four or five quarts of Cowslips pickt and cut and Stamped thin in a morter and when the water is pretty coole or blood warme put it into an earthen Stand thin put in the Cowslips and then take one Spoon full of the Yeast and the juicd of two Lemmons beat togither put that alsod into the water and let it Stand a day and two nights thin Strained it thorough a haire Sievd and thin put it into your Vessell and let it Stand very well Stopt thired weeks or a month thin bottle it and put in each bottle a lump of loaf Sugar and you may drink thin of at a months end: It will Keepe a year if you please"

Note on the Original Text

The recipe is written in a conversational, unpunctuated, and capitalization-heavy style typical of the early 18th century, intentionally brief and reliant on the common culinary knowledge of its audience. Time and temperature cues reference sensory markers like 'blood warm.' Unfamiliar spellings ('boyle,' 'pickt,' 'Stand,' 'hair Sievd') and the lack of standardized measurements reflect the oral-tradition roots of the period. The process moves from boiling and infusing, to primary and secondary fermenting, then bottling and sweetening before consumption.

Title

Cookery book of Ann Goodenough (1738)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Ann Goodenough

Era

1738

Publisher

Unknown

Background

A delightful journey into the kitchens of early 18th-century England, this collection captures the flair and flavors of its time with recipes crafted by the inventive Ann Goodenough. Expect a charming medley of hearty roasts, comforting pies, and time-honored confections, perfect for those wishing to dine as they did in Georgian days.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

This cowslip wine recipe hails from 18th-century England, a period when home winemaking was a practical skill embraced in rural and genteel households alike. The recipe can be traced to Ann Goodenough, active between 1700 and 1775, during an age when flower and herb wines were prized both for their flavors and medicinal properties. Cowslips, a now-rare wildflower, were once abundant in English meadows. Their fragrant blossoms were steeped for wine, an elegant homemade tonic and festive delight, capturing the vibrant taste of spring. Recipes like this reflect the careful resourcefulness and botanical curiosity of the Georgian era.

Wine was made in sturdy domestic kitchens using simple but effective tools: a large metal boiler or cauldron for the sugar syrup, a mortar and pestle for bruising the flowers, and a large glazed earthenware pot ('earthen Stand') or barrel for fermentation. Straining was accomplished with a horsehair sieve or fine cloth, while bottling called for glass bottles, often with cork stoppers. Fermentation relied on wild or baker's yeast, and lemon supplied gentle acidity to balance the brew.

Prep Time

20 mins

Cook Time

30 mins

Servings

45

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 3 imperial gallons water (about 13.5 US quarts or 12 US quarts plus 1.5 US pints)

- 6 lbs granulated sugar

- 9–10.5 oz cowslip flowers (or 4–5 quarts/9–11 cups primrose or edible wildflower mix, if unavailable)

- 2 lemons, juiced

- 1 tbsp (0.5 fl oz) active dry yeast or baker's yeast

- Extra granulated or loaf sugar, about 0.2 oz per bottle (about 1 sugar cube)

Instructions

- Begin by bringing 3 imperial gallons (about 13.5 US quarts or 12 US quarts plus 1.5 US pints) of water to a gentle boil.

- Stir in 6 pounds (about 13 cups) of granulated sugar and allow the mixture to boil together for 30 minutes.

- While it cools to blood temperature (about 98.6°F or lightly warm to the touch), prepare your cowslips: pluck, roughly chop, and bruise 4 to 5 quarts (loosely packed, or roughly 9 to 11 cups, or 9 to 10.5 ounces by weight) of cowslip flowers.

- If cowslips are unavailable, primroses or a mix of edible wildflowers can be substituted for aroma.

- Pour the cooled sugar syrup into a large ceramic or glass fermenting vessel.

- Add the prepared cowslips.

- In a small bowl, mix one tablespoon (0.5 fl oz or 1 tablespoon) of baker's yeast with the juice of two fresh lemons, then stir this mixture into your vessel.

- Cover the fermenter loosely and allow it to ferment at room temperature for 48 hours.

- Strain the liquid through a fine sieve or muslin cloth to remove solids, then transfer the clear liquid to a clean, airtight fermenting vessel.

- Let it stand, well sealed, for 3-4 weeks.

- When fermented, bottle the wine, placing a small piece (about 0.2 ounces) of loaf sugar or a sugar cube in each bottle.

- The wine can be drunk after one month and will keep for up to a year if properly stored.

Estimated Calories

150 per serving

Cooking Estimates

You will need about 30 minutes to boil the sugar and water, and another 20 minutes to prepare and add the flowers and lemon yeast mix. Preparing bottles takes extra time. Fermentation time is longer, but hands-on time is low. One serving is about 250 ml (a glass), and each glass contains about 150 calories.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Dietary Preference

Culinary Technique

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes