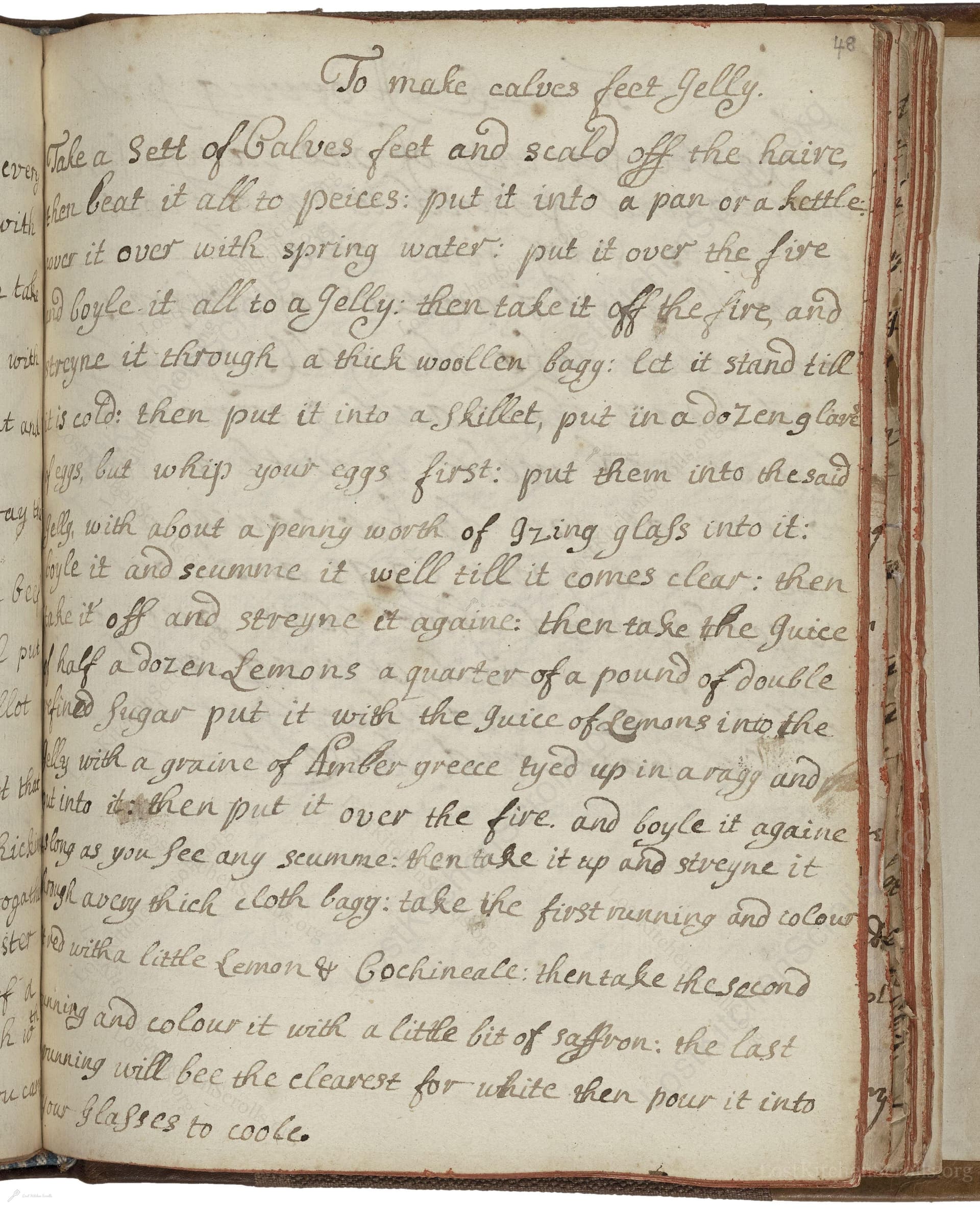

To Make Calves Feet Jelly

From the treasured pages of Cookbook of Constance Hall

Written by Constance Hall

To Make Calves Feet Jelly

"Take a Sett of Calves feet and scald off the haire, then beat it all to peices: put it into a pan or a kettle put it over with spring water: put it over the fire and boyle it all to a Jelly: then take it off the fire, and streine it through a thick woollen baggy: Let it stand till it is cold: then put it into a Skillet, put in a doZenglasses of eggs, but whip your eggs first: put them into the said Jelly, with about a penny worth of Ising glass into it: boyle it and scumme it well till it comes clear: then take it off and streyne it againe: then take the Juice of half a dozen Lemons a quarter of a pound of double refined Sugar put it with the Juice of Lemons into the Jelly, with a graine of Amber greece tyed up in a ragg and put it into it: then put it over the fire, and boyle it againe as long as you see any scumme: then take it up and streyne it through a very thick cloth baggy: take the first runing and colour it with a little Lemon & Cochineale: then take the second runing and colour it with a little bit of saffron: the last runing will bee the clearest for white then pour it into your glasses to coole."

Note on the Original Text

This recipe is written in the engaging, conversational style of the late 17th century, favoring practical kitchen English over formality. Spelling and punctuation were not standardized, leading to antique terms like 'boyle,' 'Skillet,' and 'streine.' Quantities are often approximate—'about a penny worth' and 'a graine'—reflecting both the high cost and potent nature of certain ingredients. The instruction to divide the jelly into runnings and color them separately reflects a period taste for decorative and multi-hued desserts. Clarification with egg whites and isinglass is a classic pre-industrial gelatin technique, essential for achieving the famed crystal-clear finish.

Title

Cookbook of Constance Hall (1672)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Constance Hall

Era

1672

Publisher

Unknown

Background

A spirited foray into 17th-century kitchens, this collection by Constance Hall brims with the flavors, secrets, and delicacies of Restoration-era England—perfect for cooks keen to revive a dash of history in their modern menus.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

This recipe for calf’s foot jelly was penned by Constance Hall in 1672, at a time when jelly was prized both for its delightful texture and its reputed restorative qualities. In the 17th century, such jellies were popular in the houses of the wealthy, served both as sophisticated desserts and as elegant dishes alongside meats or wines. Jellies like these showcased the cook’s skill: the process of clarifying with egg whites and isinglass was both a technical challenge and a source of pride, resulting in shimmering clear jellies in various hues. Ingredients like ambergris—a rare aromatic resin—further signaled luxury and refinement.

In the 17th century, this recipe would be prepared in large brass or copper kettles over an open hearth. Straining and clarifying was done using woollen bags, linen cloths, or thick sieves. Whipped eggs were whisked with birch twigs or bundles of fine sticks, called whisks. For delicate coloring, tiny amounts of cochineal and saffron were dissolved separately and added just before setting—in simple wooden or glass molds. Glasses used in the final presentation were tall and clear, often imported and highly valued.

Prep Time

1 hr

Cook Time

5 hrs

Servings

12

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 4 calves’ feet (about 3-4 lbs)

- 3 quarts fresh (spring) water

- 12 egg whites

- 1/4 oz isinglass (or 1/4 oz leaf gelatin as substitute)

- Juice of 6 lemons (approx. 6 fl oz)

- 4 oz double-refined white sugar

- A small pinch (about 4 grains) ambergris, tied in cloth (or a few drops vanilla)

- Few drops cochineal (or food-safe red coloring) for pink

- A pinch saffron for yellow coloring

Instructions

- Begin by thoroughly cleaning 4 calves' feet (about 3-4 lbs total), ensuring that any hair is removed.

- Chop them into small pieces and place in a large stockpot, covering with about 3 quarts of fresh water.

- Bring to a boil, skimming any impurities, then simmer gently for 4-5 hours, until the liquid is reduced and gelatinous.

- Strain this rich broth through a thick cloth or fine sieve and allow it to cool completely until it sets.

- Once gelatinized, return the jelly to a clean pot.

- In a bowl, whisk together 12 egg whites (whipped until foamy) and add them to the jelly—this will clarify the broth as it boils.

- Add about 1/4 oz of isinglass (or substitute with an equivalent amount of leaf gelatin), and bring to a low boil, skimming off any scum until the liquid is clear.

- Strain once more through a cloth for clarity.

- To flavor and finish, stir in the juice of 6 lemons and about 4 oz of finely ground white sugar.

- To capture the aromatic note, tie a small pinch (about 4 grains) of ambergris (substitute: a few drops of vanilla if unavailable) in muslin and simmer it briefly in the jelly.

- After a final boil and straining, divide the jelly: tint portions pale pink with lemon and a touch of cochineal, another delicate yellow with a pinch of saffron, and keep some uncolored for clear 'white.' Pour into individual molds or glasses and set until firm.

Estimated Calories

150 per serving

Cooking Estimates

Preparing this traditional jelly recipe takes some time, including cleaning and simmering the calves’ feet, clarifying the jelly, and letting it set. Most of the time is spent simmering the broth and waiting for the jelly to cool and set. Each serving is rich in protein and flavor, while being relatively low in calories per portion.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Dietary Preference

Main Ingredients

Culinary Technique

Occasions

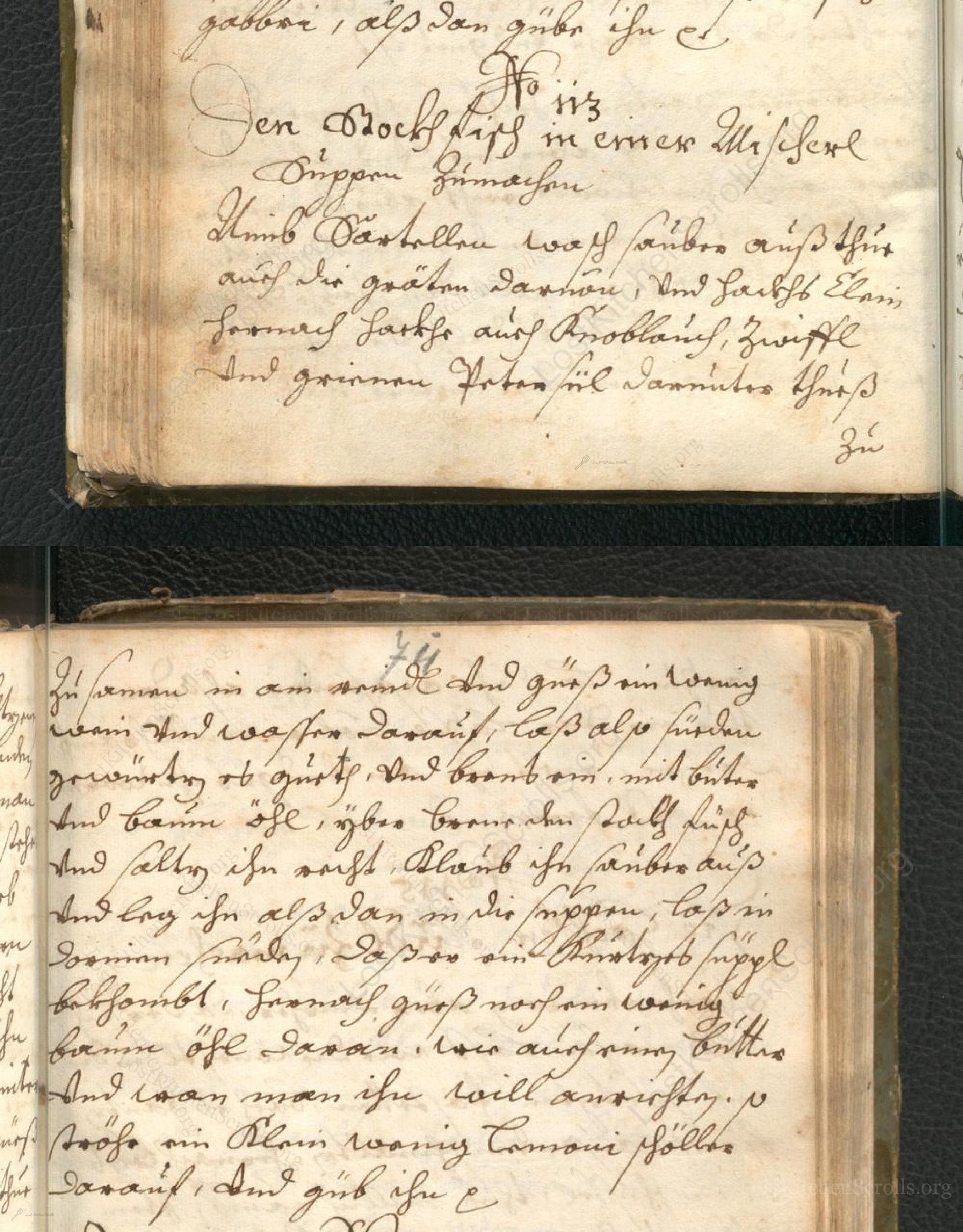

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes