Kalbsfüße Zum Gemüs

"Calves’ Feet For Vegetables"

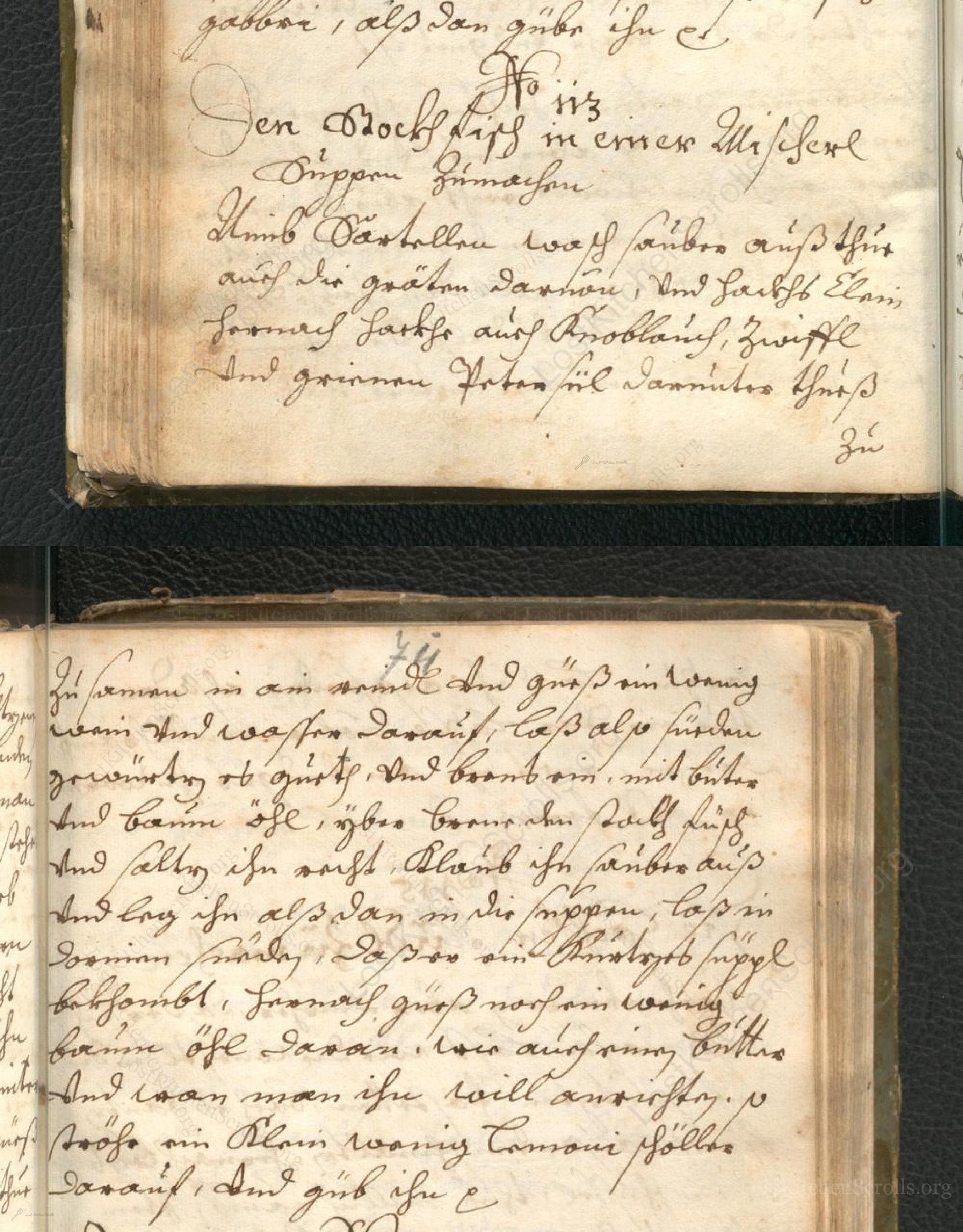

From the treasured pages of Augsburgisches Kochbuch

Written by Sophie Juliane Weiler

Kalbsfüße Zum Gemüs

"Wenn die Kalbsfüße recht sauber geputzt und gewaschen sind: werden sie in gesalzenem Wasser gesotten; und, wenn sie recht weich sind, von den Beinen, so gut als möglich, abgelöst; in der Mitte zerschnitten, dann Eyer verkleppert, die Kalbsfüße darinn umgekehrt, mit untereinander gemischtem Salz, Semmelmehl und weissen Mehl bestreut, und im Schmalz gebacken. Man kann auch einen gebrühten Teig machen, diese Füße darinnen umkehren, und langsam aus dem Schmalze backen."

English Translation

"160. Calves’ Feet for Vegetables. If the calves’ feet are properly cleaned and washed, they are boiled in salted water; and when they are very tender, remove them from the bones as best as possible; cut them in the middle, then beat eggs, dip the calves’ feet in the eggs, sprinkle them with a mixture of salt, breadcrumbs, and white flour, and fry them in lard. You can also make a scalded dough, dip the feet in it, and fry them slowly in lard."

Note on the Original Text

Recipes of this era were dictated much more by oral tradition than strict measurement, so instructions are suggestive rather than precise. The original German contains now-archaic spellings and turns of phrase—for instance, 'Gemüs.' refers simply to a prepared dish, not modern 'Gemüse' (vegetables), and 'verkleppert' means 'beaten' (as with eggs). Quantities and times are rarely exact; the cook was expected to use experience and common sense, tasting and testing doneness throughout. Modern interpretation brings precision and structure while honoring the spirit of creative and empirical cookery that defined the age.

Title

Augsburgisches Kochbuch (1788)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Sophie Juliane Weiler

Era

1788

Publisher

In der Joseph-Wolffischen Buchhandlung

Background

A delightful journey through 18th-century German cuisine, the Augsburgisches Kochbuch serves up a generous helping of traditional recipes and household wisdom, inviting readers to savor the flavors and customs of its era.

Kindly made available by

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

This recipe hails from the 'Augsburgisches Kochbuch' of 1788, crafted by Sophie Juliane Weiler, a notable writer of the era. Published in Augsburg, a city with a rich tradition of both rustic and refined cuisine, it reflects late 18th-century German cooking—a time when no part of the animal went to waste, and ingenuity in the kitchen was celebrated. Calves' feet were historically prized for both their flavor and their gelatinous texture, serving as both a humble delicacy and a practical ingredient. At the time, cooks often used what was available, and methods like breading and frying would elevate even the most modest cuts into something truly appetizing. Frying in lard was common practice, imbuing the dish with richness.

Cooks in 18th-century Germany would use a large iron or copper pot for boiling the veal feet, wooden spoons for stirring, and a knife for separating the soft flesh from the bone. The breading process happened in earthenware bowls, and frying was done in a large, heavy pan or skillet over a wood or coal-fired hearth, with animal fat (lard) used for frying. Serving might have involved simple wooden boards or plates, as tableware was practical and straightforward for everyday meals.

Prep Time

20 mins

Cook Time

2 hrs 50 mins

Servings

6

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 2.2 lbs veal feet (calves' feet), cleaned and washed

- 3 1/4 quarts water

- 1 tablespoon (0.5 oz) salt

- 2-3 eggs, beaten

- 3.5 oz white breadcrumbs

- 0.7 oz wheat flour (type 405 or 550)

- 7 oz lard (or clarified butter / neutral oil as substitute)

- Optional: batter made from flour, a little boiling water, and egg

Instructions

- Begin by thoroughly cleaning and washing approximately 2.2 lbs of veal feet (calves' feet).

- Place them in a large pot, cover with water (about 3 1/4 quarts), add a generous tablespoon of salt, and simmer for 2 to 3 hours or until the feet are very soft and the meat separates easily from the bones.

- Once cooked, let them cool slightly, then strip the meat and soft tissue from the bones as best as you can.

- Cut the pieces in half.

- In a bowl, beat 2-3 eggs.

- Dip the veal pieces into the egg mixture so that they are fully coated.

- In a separate bowl, combine 3.5 oz white breadcrumbs, a pinch of salt, and 2 tablespoons (about 0.7 oz) of plain wheat flour (type 405 or 550).

- Coat the egg-dipped veal feet with the breadcrumb-flour mixture.

- Heat about 7 oz of lard (or you can substitute with clarified butter or neutral oil) in a large frying pan over medium heat.

- Fry the breaded pieces slowly until golden brown on all sides.

- Alternatively, make a choux-style batter (blend boiling water with flour and egg to make a thick batter), dip the veal pieces in the batter, and fry slowly in the hot lard until cooked through and crisp.

Estimated Calories

450 per serving

Cooking Estimates

It takes about 20 minutes to get the ingredients ready, and about 2.5 hours to cook the veal feet until soft. Frying takes another 20 minutes. Each serving has an estimated 450 calories, and the recipe makes about 6 servings.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes