The Ground Worke For The White Japan

From the treasured pages of Receipts in cookery and medicine 1700

Unknown Author

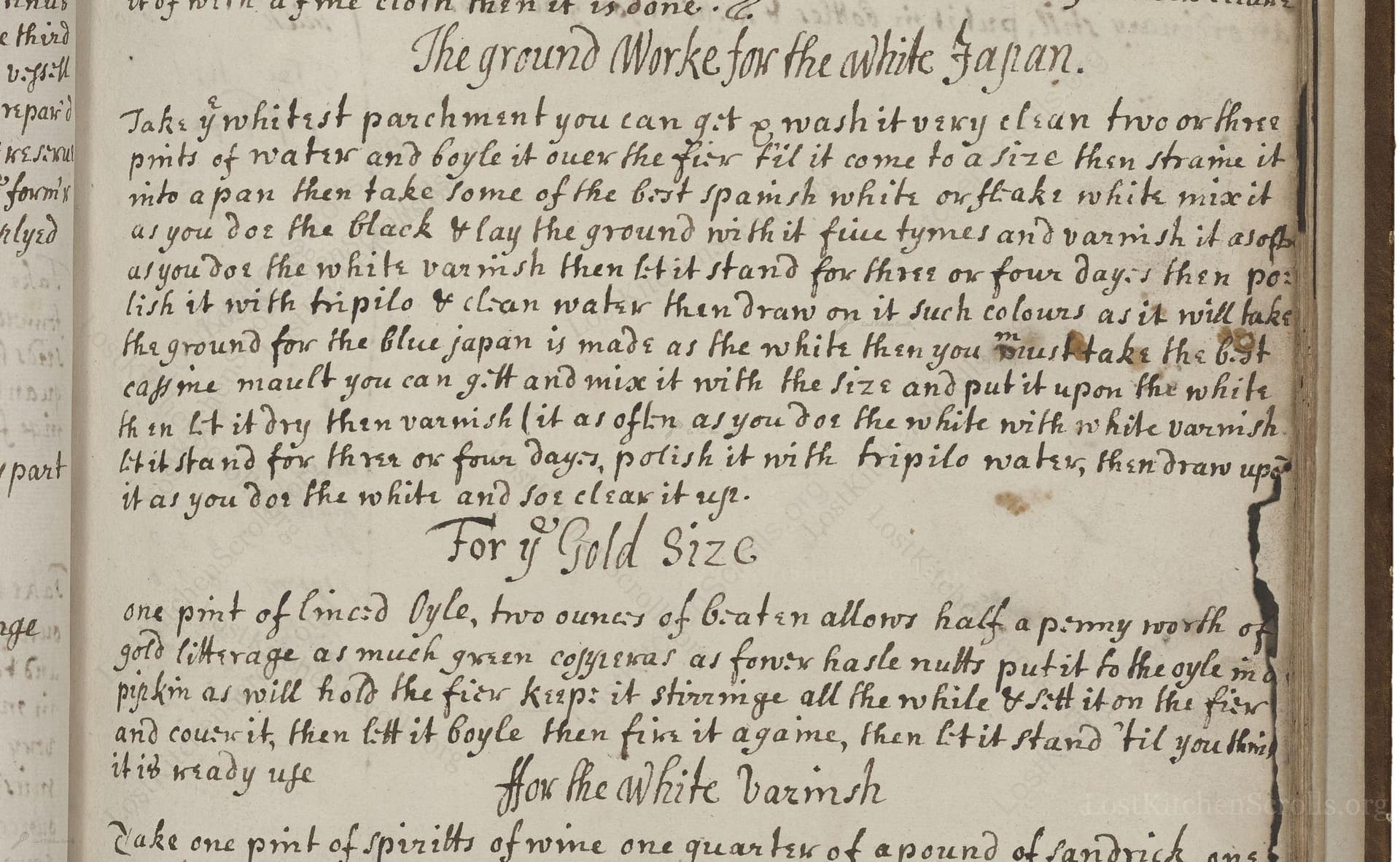

The Ground Worke For The White Japan

"Take ye whitest parchment you can get & wash it very clean two or three tymes, put one of the sheets into three pints of water and boyle it over the fire till it come to a size then straine it into a pan then take some of the best spanish white or flake white mix it with it fiue tymes and varnish it asoft as you doe the black & lay the ground with it as oft as you doe the white varnish then let it stand for three or four days, then polish it with tripilo & clean water then you must draw on it such colours as it will take the ground for the blue japan is made as the best white then you must take the best cassme mault you can gett and mix it with the size and put it upon the white then let it dry then varnish it as often as you doe the white with white varnish let it stand for three or four days, polish it with tripilo water, then draw up it as you doe the white and soe clear it up."

Note on the Original Text

The recipe is written in phonetic, early-modern English, reflecting variable spelling and minimal punctuation—common traits in manuscript instructions of the era. Terms like 'boyle,' 'straine,' and 'size' refer to boiling, straining, and gelatinous glue solutions, familiar to artisans of the day. Directions are iterative ('as oft as you doe the...'), assuming the reader's practical familiarity with standard craft routines. Descriptive rather than prescriptive, it lists steps rather than precise measurements, relying on the practitioner's judgement—a hallmark of 17th and 18th-century technical writing. The mention of 'tripilo' refers to tripoli, an abrasive for polishing, while 'cassme mault' is likely a corruption of 'cassimalt,' a blue pigment, here substituted by modern ultramarine.

Title

Receipts in cookery and medicine 1700 (1700)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Unknown

Era

1700

Publisher

Unknown

Background

Step into the kitchen of the early 18th century, where this charming culinary manuscript tempts tastebuds with recipes and secrets from a bygone era. A delicious journey for both the curious cook and the history lover.

Kindly made available by

Folger Shakespeare Library

This recipe, dating to around 1700, is a prime example of early modern English artists' and craftsmen’s efforts to create lustrous, durable surfaces for decorative arts known as 'Japaning.' Emulating fine East Asian lacquerware, the process involves building up rich, opaque grounds upon which intricate designs could be painted or gilded. The use of parchment—rich in collagen—helped create a strong gelatinous binder known as 'size,' which was prized for its smoothness and translucency. Such recipes were not for food, but for the burgeoning world of decorative interiors, furniture, and fashionable ornamentation. The inclusion of both white and blue grounds reflects the popularity of these colors in European Japonisme, mirroring Chinese porcelain and lacquer techniques.

In 1700, the process would have required a sturdy iron or brass pot for boiling the parchment, wooden spoons for stirring, and a fine muslin or linen cloth for straining the gelatinous size. Flat badger-hair brushes were used for applying both size and pigments. Polishing was performed with small cloths or pads (often linen), using tripoli powder sourced from Sicily or local suppliers. Workspaces needed to be dust-free and sufficiently warm to aid drying, with flat wooden boards or tabletops to lay out the work.

Prep Time

20 mins

Cook Time

45 mins

Servings

1

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 1 large sheet of high-quality white parchment (or ~0.7 oz unflavored gelatin sheets as substitute)

- 3 pints (6 1/3 cups) of clean water

- 0.7 oz artist-grade zinc oxide (or modern titanium dioxide as alternative to 'Spanish white')

- Tripoli polishing powder (or finest grade abrasive powder available)

- Blue pigment (ultramarine or Prussian blue), 0.35–0.53 oz (for blue version)

- Fine muslin cloth for straining

Instructions

- Begin by selecting the whitest possible parchment (if unavailable, high-quality unbleached gelatin sheets are a suitable substitute).

- Rinse the parchment thoroughly 2–3 times in clean, cold water to remove any dust or surface impurities.

- Place one sheet (about 8 x 12 inches) into roughly 3 pints (6 1/3 cups) of water in a saucepan.

- Bring to a gentle boil on medium-low heat for about 45 minutes, or until the water reduces to a thick, gelatinous consistency (known as 'size').

- Strain this mixture through fine muslin into a clean pan to ensure clarity.

- In a separate bowl, mix approximately 0.7 ounces of fine artist-grade zinc oxide (for 'Spanish white' or flake white, which historically referred to basic white pigments) with some of the prepared gelatin size.

- Blend thoroughly and repeat this mixing five times to ensure an even and creamy texture.

- Brush this mixture evenly onto your prepared surface (wood, paper, or panel), applying as many layers as you would typically do when varnishing (usually 3–4 coats), allowing each layer to dry partially between coats.

- Leave the coated surface to cure for 3–4 days.

- Once fully dry, polish delicately with a very fine abrasive (modern equivalent: tripoli polishing powder with a few drops of clean water) to achieve a smooth, lustrous finish.

- At this stage, you may paint upon the ground using compatible pigments.

- For the blue version, repeat the above steps for the white base, then mix a premium ground blue pigment (such as ultramarine or Prussian blue) with the size.

- Coat this carefully over the white ground, dry, and varnish as before.

- Allow 3–4 days to cure and finish with a light polish.

- You may then proceed to decorate with further colors as desired.

Cooking Estimates

Preparing and extracting the gelatin size, mixing pigments, applying multiple layers, and letting each coat dry takes several hours over a few days. Most of the time is spent waiting for layers to dry and cure. There are no calories in this recipe, as it is not food.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes