Hammels-Würste

"Mutton Sausages"

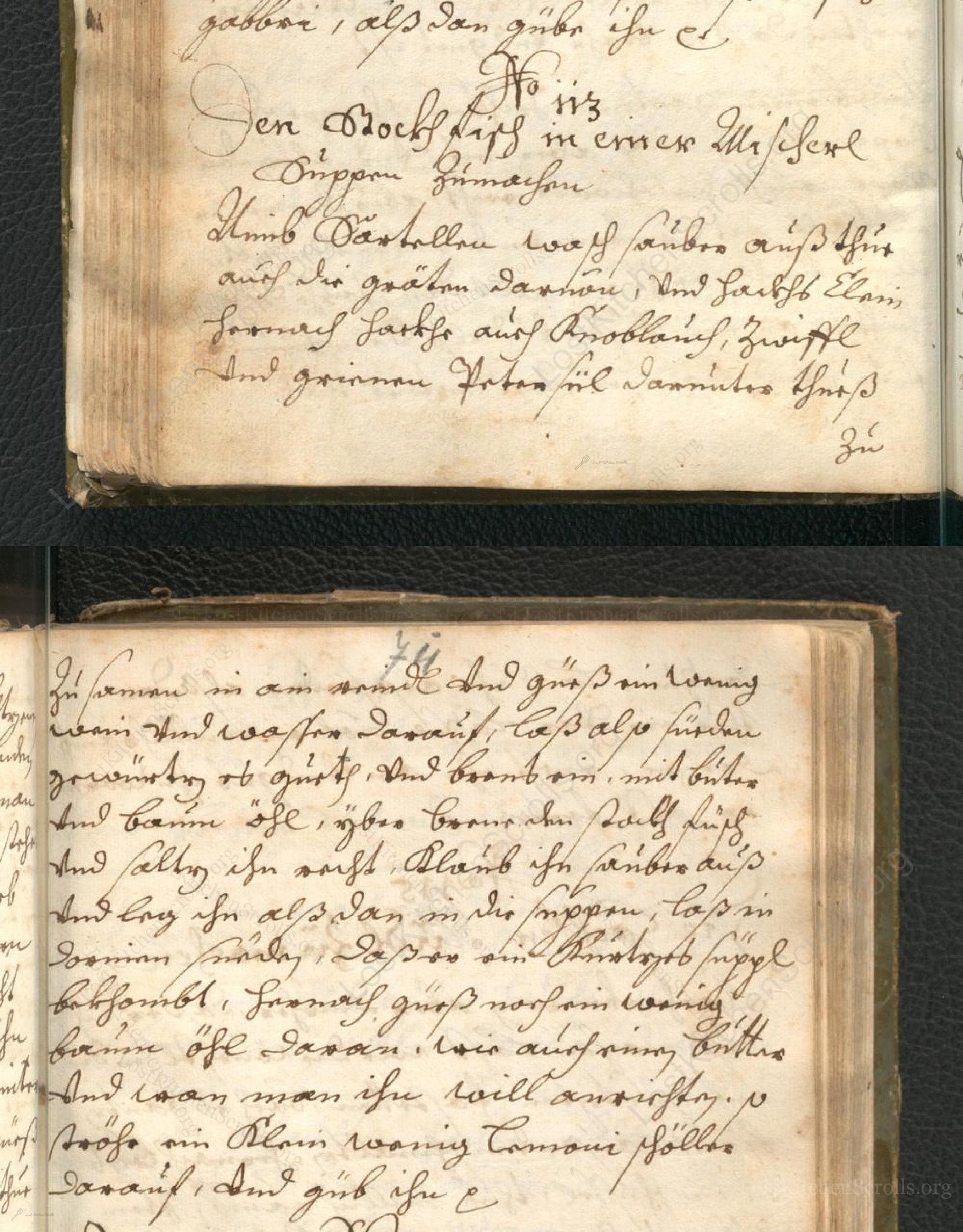

From the treasured pages of Augsburgisches Kochbuch

Written by Sophie Juliane Weiler

Hammels-Würste

"810. Hammels-Würste. Man läßt Hammels Blut durch einen Sey: her laufen. Alsdann wird so viel gute Milch, als der dritte Theil vom Blut ausmacht, dazu genommen, eine klein geschnittene Zwiebel in Butter gedämpft, nach Gutdünken gestoßene Nägelein, Pfeffer, Ingwer, Salz und Majoran dazu gethan; dieses alles untereinander gemacht, in sauber geputzte Hammelsdärme gefüllt, und in heißem Wasser verwällt. Dieses muß aber immer nur am Sieden seyn. Wann man in eine von den Würsten hineinsticht, und es läuft kein Blut mehr heraus: so sind sie fertig. Man kann auch Brosamen von weissem Brode, recht klein verzopft, in Milch einweichen, und unter das Blut rühren."

English Translation

"810. Mutton Sausages. Let the mutton’s blood run through a sieve. Then take as much good milk as makes up a third of the blood’s volume, add an onion finely chopped and sautéed in butter, some ground cloves, pepper, ginger, salt, and marjoram to taste. Mix all this well, fill into carefully cleaned mutton intestines, and poach in hot water, always keeping it at a gentle simmer. When you prick one of the sausages and no more blood runs out, they are done. You can also soak breadcrumbs from white bread in milk, crumble them very finely, and stir them into the blood mixture."

Note on the Original Text

The recipe is written in the precise-yet-loose style of early modern German cookbooks: measurements are more proportional than exact (e.g., 'the third part of the blood'). Instructions relied on assumed kitchen knowledge (e.g., recognizing when sausages are cooked). Spelling varies due to 18th-century conventions: 'verzopft' likely refers to beaten or separated, 'Seyher' means sieve, and 'verwällt' indicates gentle poaching, not boiling. The casual use of words like 'nach Gutdünken' ('to taste') shows the trust placed in the competent cook’s judgment.

Title

Augsburgisches Kochbuch (1788)

You can also click the book image above to peruse the original tome

Writer

Sophie Juliane Weiler

Era

1788

Publisher

In der Joseph-Wolffischen Buchhandlung

Background

A delightful journey through 18th-century German cuisine, the Augsburgisches Kochbuch serves up a generous helping of traditional recipes and household wisdom, inviting readers to savor the flavors and customs of its era.

Kindly made available by

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

This recipe hails from the 'Augsburgisches Kochbuch', published in Augsburg in 1788 by Sophie Juliane Weiler—a remarkable example of upper middle-class German cookery from the Enlightenment era. The cookbook is a testament to the resourcefulness and delicacy of late 18th-century German cuisine, where no part of the animal was wasted and fresh flavors were celebrated. Mutton (or sheep) was a common staple in central Europe; sausages such as these were often made directly after slaughter, traditionally by women in the household, preserving nutrition and flavor. Blood sausages were especially popular in rural and urban kitchens alike as they were filling, nutritious, economical, and could be adapted with regional herbs.

Historically, a heavy wooden or earthenware mixing bowl was used for blending the blood, milk, and seasonings. A sieve (often horsehair or linen) served to strain the blood. Onions were sautéed in a metal or ceramic pan over an open fire. The sausage casings were painstakingly cleaned with running water and salt, often using special slim, rounded sticks or metal rods. For stuffing, a simple funnel or handmade horn, or a wooden sausage stuffer, was used. Poaching was done in a large cauldron or kettle of water suspended over the hearth. Pricking the sausage was done with a sharp needle, fork, or slender wooden skewer.

Prep Time

1 hr

Cook Time

45 mins

Servings

8

We've done our best to adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, but some details may still need refinement. We warmly welcome feedback from fellow cooks and culinary historians — your insights support the entire community!

Ingredients

- 1 quart fresh sheep (mutton) blood (or substitute with pig blood if unavailable)

- 1⅓ cups whole milk

- 1 medium onion (about 3.5 oz), finely chopped

- 1 tbsp (0.5 oz) unsalted butter

- 1/2 tsp ground cloves

- 1/2 tsp ground black pepper

- 1/2 tsp ground dried ginger

- 2 tsp salt (to taste)

- 1 tbsp dried marjoram (or fresh, finely chopped)

- Optional: 1.75 oz white bread crumbs, soaked in an additional ⅓ cup milk

- About 6½ feet cleaned sheep intestine casings (sub: pork casings or synthetic sausage casings)

Instructions

- To create these 18th-century mutton blood sausages, start by carefully sieving freshly collected mutton blood to remove any clots or impurities.

- For every 1 quart of blood, add approximately 1⅓ cups of whole milk.

- Gently sauté one finely chopped onion in a tablespoon of butter until translucent.

- Add the sautéed onion, along with ground cloves, pepper, ginger, salt, and dried marjoram to your taste into the blood-milk mixture.

- Optional: For a lighter texture, soak about 1.75 ounces of fresh white breadcrumb crumbs (preferably from a sturdy loaf or brioche) in warm milk, then fold into the blood mixture.

- Using clean, soaked mutton or sheep casings, carefully stuff the mixture into casings, tying off at regular intervals.

- Bring a large pot of water barely to a simmer (not a rolling boil!), and gently poach the sausages.

- Test for doneness by pricking one: when the liquid runs clear (not bloody), the sausages are ready.

- Let them cool before serving or searing for a crisp exterior.

Estimated Calories

200 per serving

Cooking Estimates

Preparing the ingredients, including sautéing the onion and soaking the breadcrumbs, takes about 30 minutes. Stuffing the casings may take another 30 minutes. Poaching the sausages gently until done usually takes about 45 minutes. One batch makes around 8 sausages, serving 8 people. Each serving contains about 200 calories, based on the typical ingredients used.

As noted above, we have made our best effort to translate and adapt this historical recipe for modern kitchens, taking into account ingredients nowadays, cooking techniques, measurements, and so on. However, historical recipes often contain assumptions that require interpretation.

We'd love for anyone to help improve these adaptations. Community contributions are highly welcome. If you have suggestions, corrections, or cooking tips based on your experience with this recipe, please share them below.

Join the Discussion

Rate This Recipe

Den Bockfisch In Einer Fleisch Suppen Zu Kochen

This recipe hails from a German manuscript cookbook compiled in 1696, a time whe...

Die Grieß Nudlen Zumachen

This recipe comes from a rather mysterious manuscript cookbook, penned anonymous...

Ein Boudain

This recipe comes from an anonymous German-language manuscript cookbook from 169...

Ein Gesaltzen Citroni

This recipe, dating from 1696, comes from an extensive anonymous German cookbook...

Browse our complete collection of time-honored recipes